“Imagination is more important than knowledge. For while knowledge defines all we currently know and understand, imagination points to all we might yet discover and create.” — Albert Einstein

This summer, I attended a Creative Problem Solving Institute workshop on creative problem solving (CPS), presented by the Creative Education Foundation. I asked three CPS specialists—all current or former QRCA members—to share their perspectives on how we can leverage this intriguing mix of mindset, process, and skills to broaden and enrich our qualitative practice. Here’s what these practitioners had to say.

— Schools of Thought Feature Editor Tamara Kenworthy

What Is Creativity?

What Is Creativity?

My favorite definition (from psychologist Rollo May) is, “Creativity is the production of novel and useful ideas in any domain.” Useful ideas. Any domain. That means our domain too—qualitative market research.

Why Do We Need Creativity in Qualitative Research?

Have you ever found yourself ready to create a discussion guide and wishing you were inspired to include something different? Hoping to craft a question or a projective exercise that would be new, and therefore intriguing, for your client? Or maybe you’ve found yourself wishing for something to spice up your client debriefs or to break through a panic-inducing case of writer’s block. Creativity in qualitative research allows us to bring new ideas to the work we do and the ways we deliver insights to clients. It allows us to express novelty in our deliverables. It also positions qualitative researchers as imaginative forces in a world of big data and statistics.

What Gets in the Way of Being Creative?

Any list of barriers to creativity can be a long one. Fortunately, CPS is a powerful tool to help us overcome barriers to unleashing our creative, imaginative potential in our qualitative practices.

- There’s a misconception that some people are just not creative. Well, that’s just wrong. Yes, some people are innately disposed to creating things out of passion or personality, but what about the rest of us? We just need to be freed from limitations, from experiences that stifled our creativity in our childhoods, and given tools to let our innate creativity manifest itself in all we do.

- Some state they don’t have the time to be creative—they suffer from a desire to get things done and don’t want to take the time to stretch their minds. Better deliverables will make it worth the time it might take you to think creatively. Creativity is a skill that can be practiced, and in time, will come much faster!

- Habits are in place that prohibit us from being imaginative. Imagination is a process that leads to the mental formulation of images or concepts. So, if accessing your creativity is not habitual, you won’t leverage imagination routinely.

- Fear of failure and/or judgement is one of the hardest hurdles to overcome. Many human beings are inherently timid and afraid to try new things and put themselves out there. It takes self-confidence to leap over this one… and where do we get that confidence from? Practice (and we’ll show you how later in this article). In creative circles, we also celebrate failure… because without it we don’t grow (but that’s a topic for another article).

- We lack the tools needed to be creative. The rest of this article is focused on Creative Problem Solving (CPS)—as a process, a framework. CPS is a set of tools that can be leveraged to overcome this last hurdle, as well as all the other ones.

The Dynamic Balance of Imagination,and Judgement (or Divergent and Convergent Thinking)

We aren’t used to separating the tasks of using our critical, judgement mindset from our imaginative, creative mindset. Alex F. Osborn, the “O” in the iconic advertising firm BBDO, explains this beautifully in his ground-breaking book, Applied Imagination, first published in 1953. “We allow ourselves to be creative and self-critical at the same time… it is a little like trying to get hot and cold water out of the same faucet at the same time: the ideas may not be hot enough, the evaluation of them not cold or objective enough. The results will be tepid.”

When we keep our use of imagination and judgement in check—alternating between these two mental processes—we leverage the full potential of CPS. First, we allow our creative mind to visualize, foresee, and generate ideas. We allow it to enlighten us and then tap into our judicial thinking to analyze, compare, and choose. We use judgement to keep our imagination in check. It’s a dynamic balance that makes all the difference in how we approach our creative efforts. And it’s a polarity, like breathing in and breathing out; we need both to live.

In CPS, it is understood that we need both imagination and judgment to yield a creative output. Switching from an imaginative to a judgmental mindset is fundamental to being able to apply CPS’s divergent and convergent tools. CPS practitioners rely on the creative problem-solving process to overcome the barriers to creativity. As a result, we create breakthrough ideas and solutions on behalf of our clients.

Creative Leaders Know How to Solve Problems

Let’s face it: the qualitative research industry has changed, and it’s never going back to the way it was. It’s not enough to be highly skilled in digging for insights; clients demand qualitative partners who step out of their comfort zones and demonstrate strong strategic and creative leadership in every aspect of a project.

A fast track to this type of leadership is Creative Problem Solving (CPS). According to CPS pioneer Alex Osborn, creative thinking transcends age, gender, and education, and is largely a function of effort. Creative thinking is the first step toward creative leadership, a step that will propel you into the role of strategic partner, transcending the client-consultant hierarchy. The best definition I’ve heard for Creative Problem Solving comes from a creativity colleague, Jody Reed Fisher, who explains, “CPS is a mindset, a process, and a set of skills. Mindset can be grown, process can be applied, and skills can be mastered.” The purpose of CPS is to solve problems. In CPS, a problem is defined as any area requiring new thinking and imagination. You might call it a challenge, a wish, or an opportunity.

Grow Your Leadership—and Research Skills—Through the CPS Process

Grow Your Leadership—and Research Skills—Through the CPS Process

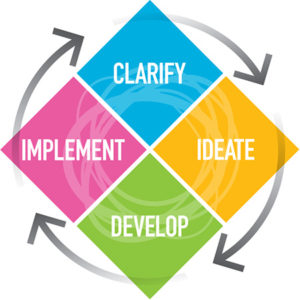

Highly effective leaders articulate a clear vision for achieving a desired outcome. In CPS, this clear vision is focused on a four-stage process: Clarify, Ideate, Develop, and Implement.

Ever wonder how CEOs become successful? Staying in a problem-solving process is the key to thinking like a CEO. And, focusing on the CPS process gives you credibility to expand your capabilities beyond traditional qualitative methods. I find myself leading larger and more strategic assignments by simply asking the question, “Where are we in the process?” This question reveals unknowns and assumptions that the consultant can then help address. And, clients will start to rely on you for problem-solving direction.

You can use this four-stage model, in sequence or separately, to identify and recommend the most strategic methodology for your clients. For example, if my clients want to evaluate concepts, which typically falls into the development stage, I ask if they have clarified the target’s needs and behaviors. If the answer is no, I recommend starting with an exploratory insights phase prior to concept evaluation. The outcome yields more solid, consumer-driven concepts. In situations where a client is seeking new ideas, I recommend an innovation process designed to generate lots of ideas across different categories, instead of focus groups.

Here are some ideas on how you can incorporate these four steps into your research projects:

Clarify

Clarify means making sure we are tackling the right problem. When clarifying the challenge, goal, or wish, practitioners will gather data and explore their clients’ vision to understand the contextual dynamics that have an impact on environment, category, and brand. If a client needs to clarify, recommend exploratory methods and techniques such as ethnography, journaling, shop-alongs, group mind mapping, that are designed to uncover the situation (not solve it).

Ideate

Ideation comes after clarifying! Here, you generate lots of ideas to address your challenge. Ideas must come from lots of sources, across categories, etc. Remember, ideas are not solutions; they are sparks to be flamed. Ideation uses specific innovation tools and techniques.

Develop

Developing means refining ideas and creating solutions. Most qualitative methods work well; the key is to seek ways to strengthen solutions and identify pitfalls. For instance, when doing concept evaluation, work to improve all concepts—regardless of whether the consumers accept or reject them.

Implement

After you have developed a solution, it’s time to put together an action plan and implement. Types of projects that fall within this stage include facilitating strategic planning sessions, advertising and communications testing, and ongoing monitoring.

The more skilled you become in applying the CPS mindset, process, and skills, the more ingrained your level of creative and strategic leadership becomes. You naturally see challenges through a strategic lens and develop the confidence to guide clients toward new thinking and viable solutions.

Using the “Invitational Language” of CPS

As a regular practitioner of the Creative Problem Solving (CPS) process, I found the specific language used throughout this process has wormed its way into my skull. Language is a critical element of CPS and is applicable to many situations.

As a regular practitioner of the Creative Problem Solving (CPS) process, I found the specific language used throughout this process has wormed its way into my skull. Language is a critical element of CPS and is applicable to many situations.

Over the years, I’ve found myself using this language more often in my qualitative research projects. Let me be clear: I am not facilitating every client team or focus group through the CPS process. Rather, I find the invitational language stems cropping up in a variety of ways.

According to the Creative Education Foundation, specific language is used at different stages of the CPS process to prime the brain to enable novel, useful options and ideas. A key example of this specificity of language is the invitational language stems we use in the process.

Invitational language literally invites us to open our thinking in creative, divergent ways. What follows are examples of applying invitational language stems in the various stages of the CPS process.

In the Clarify stage, to get a tight handle on the actual problem or challenge, it helps to use invitational language such as How might we? and What might be all the ways? These phrases lead directly into more divergent thinking—we’re not looking for a single solution but staying open to lots of ideas. Compare these stems to more closed language such as What are our objectives? or How are we going to solve this? Neither of these phrases leaves the door open to divergent, blue sky thinking.

During the CPS process, after converging at the end of the Ideate stage, it’s useful to complete the sentence, What I see myself doing is… This is one of my favorite language stems; it invites a single, unifying solution made up of the great ideas that were just generated and creates momentum to move forward to action.

In client conversations, there is efficiency in using clarifying language stems to set research objectives and methodology. Starting with It would be great if… statements about what they want to learn, we eventually get to How to and How might we as we design the research itself. Toward the end of the project, we come back to those wonderful Develop phrases such as How to and How might we. These bring the team into the frame of mind that they can overcome further challenges and create plans for action.

One of the most effective areas to use invitational language in qualitative research is within the discussion guide itself. Respondents want to help; they are looking to provide useful content for the client. When we open up the language and allow them to offer ideas and solutions, it becomes a mutually beneficial relationship. I don’t think I’ve written a discussion guide in the past 10 years that doesn’t include the phrase, In what ways might we. Inviting the respondent to articulate his or her own challenges, unmet needs, and issues within a category allows for a deeper discussion and better insights. Using these invitational language stems is a fast, efficient way to dive into that articulation.

The CPS process and invitational language can help from early stages of project design through streamlining report writing. When writing my reports, I ask myself, How might I distill this information? I also think about my conclusions and recommendations in terms of How to and use respondent quotes and behaviors to answer those questions.

Throughout the life of a qualitative research project, CPS language is extremely useful. It creates shortcuts to eliciting the kinds of thinking you want from clients, respondents, and yourself.

It creates a framework around the project elements that invites new thinking and keeps options open until it’s time to converge. Becoming fluent in CPS-style invitational language is not difficult. Once you learn the phrases and how they’re best used, you’ll likely find yourself using them all the time—and not just in a “work” context. Just ask my kids how often I’ve said, “What might be all the ways you could not be bored right now?”

Be the first to comment