What Is Mystery Shopping?

In simple terms, mystery shopping is feedback from shoppers of their experience interacting with a company’s contact centre representatives, sales reps, and other front-line staff.

Types of Mystery Shopping

Essentially there are two types of mystery shops—large audits and special shops. The latter is where qualitative researchers have an opportunity to expand their toolkits.

Large audits:

- are typically conducted for national retail chains, where most if not all the outlets are shopped on a monthly or quarterly basis;

- assess the basics in customer experience, e.g., store appearance, signage and service; as well as

- require extensive shopper support and software resources, given that 1,000 or more shops are frequently completed.

Special shops:

- are usually one-off studies that supplement other research findings (e.g. competitive intelligence, focus groups, customer satisfaction);

- focus on higher-level themes such as uncovering competitors’ best practices or assessing staff compliance in following new legislation; and

- include both B2B and consumer scenarios.

While the sample size for special shops is often less than 50, the amount of detail is extensive. For example, 20 commercial bank shops could very well entail documenting over 40 hours of real-life bank experience (i.e. accounting for scheduling the appointments, having one or two bank appointments and a follow-up after each appointment). Examples of scenarios falling under special shops are:

While the sample size for special shops is often less than 50, the amount of detail is extensive. For example, 20 commercial bank shops could very well entail documenting over 40 hours of real-life bank experience (i.e. accounting for scheduling the appointments, having one or two bank appointments and a follow-up after each appointment). Examples of scenarios falling under special shops are:

- a telecom wanting to see what other incentives competitors are offering smartphone buyers besides those listed on websites;

- a dog food company needing evidence to support why complaint resolution has been rated poorly by customers; and

- a car manufacturer having to determine whether increasing point of sale support for their dealers will offset recent sales erosion.

Hence special shops are a higher level of mystery shopping that requires the skills and experience of a market researcher or analyst to deliver the needed critical analysis, interpretation and recommendations. A vendor of large audits simply will not cut it.

Mini Case Example of How a Qualitative Project Might Evolve into a Special Shop

You recently completed a focus group to gain insights on how your bank client can speed up migrating customers from branch banking to digital. One issue that kept being raised by participants was the frequent lack of interest by branch staff to walk customers through the mobile app when a customer asks for help. What better way to get clarity of this issue than to conduct a mystery shop by assessing five client branches and five competitor branches?

To do this, recruit four colleagues. Including yourself, this would work out to each researcher doing two shops. One shop would be as an actual customer of one bank and the other as a potential customer of another bank.

Assume you would need to pay each shopper for their efforts. For example, a simple shop might involve presenting as a walk-in customer inquiring about mortgages, while a more complicated shop might involve actually signing up for a line of credit. In the case of the mobile bank shop, paying a smaller fee per shop may suffice because it would simply involve walking into the bank and asking how to use the bank’s mobile app.

Mini Case: Mystery Shop Survey

A simple template to follow for putting together a survey appears below. Essentially the survey needs to capture most of the information with a “Yes” or “No” answer. Specific rationales include: Answering “Yes” or “No” forces the shopper to make a choice, rather than rating an item on a scale of 1 to 10. Second, you are asking the shopper to feed back a lot of information and to remember this while doing their shops. So you want to make it easy and intuitive for the shoppers when answering questions. Third, for those who are familiar with Excel, “Yes” answers can be tabulated each as “1” and “No” answers each as “0”, so it is a simple matter of totaling the number of “Yes” answers to get an overall score. For example, the total number of “Yes” answers out of a possible 15 questions questions for 1 representative was 12, so they rated 80% (12/15), arguably a good performance, whereas in another survey the total number of “Yes” answers for a representative was 3/15 or 20%, a very poor performance. Excel also has an easy charting feature which provides a quick visual record that is useful in the analysis discussed later.

The survey also allows for shoppers to provide subjective comments (under “Net Impressions”). Here you can ask such questions as: “If this were a real situation, would you purchase the product based on your shop experience? Why/why not?”

Making Sense of the Data

Editing the surveys is absolutely critical because the shopper’s credibility is at stake. Scrutinize their responses carefully. Use common sense to flag any response that does not sound right. For example, conflicting information, lack of detail and rushed responses are flaws I frequently find.

Conflicting Information

In this case, one response conflicts with another. For example, the shopper indicating a “yes” to the question, “Did the rep cite any advantages of their bank’s mobile app?”, comments later in the survey that the rep made no effort to promote the mobile app. Here, email the shopper and confirm answers to the questions where responses conflict. (NOTE: permission for any needed follow-up is secured during the screening process.)

Lacking Detail

The shopper answers the question, “Do you have any suggestions on how the rep can improve their sales delivery?” simply with “try harder,” instead of noting specific suggestions about what the representative needs to do, like: make an effort to walk the customer through the app. When this happens, contact the respondent and ask for examples that illustrate the written response.

Rushing Survey

The shopper answers “Yes” to every question or writes identical comments for questions asking, “please comment”. In this case, phone the respondent and go through every survey question to make sure to capture accurate and detailed information.

When reporting, cite shopper comments that point to either very positive or very negative experiences. I look for comments that I can incorporate into a SWOT analysis. Each comment I pull reflects either a strength, weakness, opportunity, or a threat. And, I limit the number of comments to twenty (to avoid overloading the reader), using a call-out for each comment.

Once the data are tabulated and comments extracted, the analysis takes place. This is the easiest part of the assignment, given that you already have the comments as well as charts from which to draw insights.

Example Findings

Example Findings

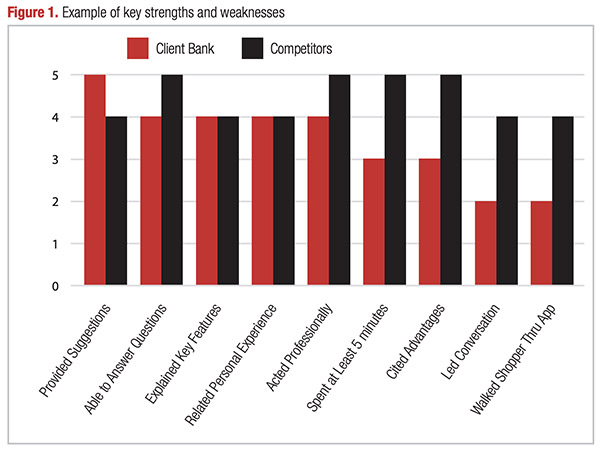

Figure 1 is an example of what might appear on a slide highlighting key strengths and weaknesses of the client bank’s branch staff efforts:

Key Strengths/Weaknesses

- Most Client Bank reps provided suggestions (e.g. avoid using app in public Wi-Fi), answered questions, explained features (e.g. deposit cheques, transfers), related their own experiences using the app, and acted professionally.

However, just two out of six reps led the conversation or walked the shopper though the client bank app.

- And only half spent at least 5 minutes discussing the app or mentioned an advantage.

- Competitor reps outperformed the Client Bank on these latter four metrics.

Tips for Conducting Your First Mystery Shop

- Be hands-on. You will need to do some shopping yourself. This not only enables you to add some personal observations and insights based on your shop experience, but also strengthens the credibility and authenticity of your shopper briefing and your results.

- Prepare to both brief your shoppers on the shop (to ensure they fully understand what to assess and the detail of information they need to record) and then debrief them (to make sure what they observed has been thoroughly and accurately communicated). So in addition to the survey, put together shopper instructions, guidelines and scenarios. A good idea is to include a completed survey as an example for shoppers to follow.

- Recruit credible shoppers as this is a key factor for success. This means recruiting shoppers who meet very specific criteria. For example, the shop may require high net worth bank customers or patients with specific medical conditions.

- Dig deep in analyzing your findings. For example, if you are undertaking a competitor shop then you should draw insights on the competitor’s:

- best practices to adapt;

- weaknesses to leverage to your client’s advantage;

- unique product features to benchmark against, and hence see where your client might fall short;

- key selling messages to counter; and

- pricing to see whether the client is above, below or on par with their competitor’s pricing.

(Sometimes I will go over a shopper survey three, four or even five times to uncover clues and to connect the dots.)

- Clients pay close attention to shopper comments, so pulling out four or five telling comments is a must. (or, must-do.) A good place to look are the shoppers’ answers to the survey questions, “What impressed you by how you were helped?” and “What did you dislike?”

- If, in addition to slides, a report is required, then create two reports. The first is the analysis, e.g. key findings, implications and recommendations. The second contains completed surveys and any other details like copies of competitor’s literature. A report with both the analysis and completed surveys is much too much for one to absorb.

Conclusion

Qualitative market researchers are in a unique position to add mystery shopping to their toolkits. Not only do they possess the necessary skills to conduct high level shops, but when done in conjunction with other research they are conducting, mystery shopping helps to corroborate findings, and it also fills in gaps and deepens one’s overall understanding of the issues being studied. Think of mystery shopping as investigative research, where one is in the field gathering intelligence and insights.

These high-level shops require the skills and experience of a market researcher to deliver the needed critical analysis, interpretation, and recommendations. They also offer qualitative researchers an excellent opportunity to expand their service offerings.

Be the first to comment