By Zoë Billington, UX Research & Customer Insights, Los Angeles, California, zbillington@gmail.com

This quarter, I met with Mark Earls, a leading thinker about brands, marketing, and mass behavior. He has held senior positions in some of the largest communications companies in the world—his last job was as chair of Ogilvy’s Global Planning Council, prior to that he was planning director at the revolutionary St. Luke’s Communications in London. His first book, Welcome to the Creative Age, was widely read and discussed and has been translated into several languages. His subsequent book, HERD, has received recognition and praise in a number of fields, and Earls has travelled extensively to talk about HERD with audiences drawn from both the business and the public sector. He has collaborated with leading social scientists to develop a usable map of human decision styles that better reflects reality (“I’ll Have What She’s Having” and “Copy, Copy, Copy”). He now advises a number of major organizations and helps them put this “better map” to work to solve their problems— in marketing, innovation, and most significantly, behavior and culture change.

Zoë Billington: Let’s start off with the 10,000-foot view of your career. How do you tell the story of what you do today and how you got there?

Zoë Billington: Let’s start off with the 10,000-foot view of your career. How do you tell the story of what you do today and how you got there?

Mark Earls: I spent the first half of my career in advertising and marketing, but I’ve been working independently as a consultant for nearly two decades now.

Looking back, it’s hard to see if I had this career in mind. I studied philosophy and German, only slightly connected to what I do now. How I got here involves a series of switchbacks and unintended consequences. At college, I had a good friend, Jamie, and he was the poshest person I’d ever met, the most aristocratic; he had one of those floppy posh boy fringes with blonde hair, and he taught me how to drink martinis. I was going to do a doctorate, and he got a job in advertising. Six months later, he called up and said: this advertising thing, it’s not for me, but I think you’d love it. So, I found myself at Grey Advertising in London, where they rotated us around a training program. I landed in the Planning and Research Department first, and I loved it. I spent hours online accessing TGI, a database of historical usage and attitude studies; within 10 days of starting my first job in advertising, I was running a focus group. I discovered I was passionate about the understanding of people, how to get closer to them, and how to communicate back the insights that you gain from interacting with the people your client’s business is serving.

So, that’s where the bug started, and then I went through various ad agencies, rising up the greasy pole. I was very lucky to have mentors like Paul Feldwick, Wendy Gordon, and Andrew Ehrenberg. Then, when I found myself running teams, teaching, and training people, it became clear that I found it difficult to clearly articulate what I thought. I became more and more frustrated with the current models and practices, and I experimented with other, newer ones. I ended up being one of the very first people to introduce what we know today as behavioral economics into the U.K.

Then, I jumped out of the world of advertising and set up on my own, because I realized that I wasn’t really as interested in advertising, or the external, exogenous interventions we place on humans. I was interested in people and what resonates in their world, and all the other ways their behavior is shaped. I’d been writing a book called Herd: How to Change Mass Behaviour by Harnessing Our True Nature, and I found myself with a point of view that was very timely in 2005. Facebook’s Zuckerberg was still in high school, the social web was in its infancy, and I was struck by how obsessed the Anglo-Saxon world is (North America and the U.K.) with what goes on between people’s ears. But in other cultures, and certainly in other sciences beyond cognitive psychology labs, the focus is on the importance of other people in shaping human behavior. Demanding that shift of focus—from the role of the individual in decision-making to the role of social factors in decision-making—became my battle cry. I spent 15 years arguing about and defining ways to make our social selves part of both the insights practice in marketing and advertising, and then also in the broader world of behavioral change.

Zoë: I want to get more into your battle cry, as first introduced in Herd. To get into that, can you take a step back and tell me more about the models of thinking you first got frustrated with in the advertising world and why that pushed you out on your own?

Zoë: I want to get more into your battle cry, as first introduced in Herd. To get into that, can you take a step back and tell me more about the models of thinking you first got frustrated with in the advertising world and why that pushed you out on your own?

Mark: Let’s start simple. In the West, we have a foundational belief that we as humans are—or should be—rational creatures, that we make decisions on our own, based on the information that’s presented to us. When we are asked why we do something, we’ll create a reason that sounds quite logical and sensible; we don’t want to admit the importance of emotion. But it became clear to me that emotions are very important, as is the influence of others, and that those were being left out of the equation.

Back in the ’80s and ’90s, there was a huge debate in research, advertising, and marketing circles about emotions or rationality, as if you had to choose one or the other. Models like the AIDA model—which stands for awareness, interest, desire, and action—were common with their discrete logical steps that a human is supposed to make toward a decision. It’s still alive today in business frameworks like the sales funnel: a procession of steps you have to go through to get to a purchase or drive a sale. It’s very useful for sales, marketing, and communications teams in ordering tasks, messaging, and ad planning, but it assumes a number of things that are wrong, not least of which is that we’re organized and coherent in our decision-making; again, we like to think we are, but we’re not. We’re messy, we’re intuitive, we’re not logical. Indeed, we think much less than we think we think. To paraphrase Daniel Kahneman, we are to thinking as cats are to swimming: we can do it if we really have to, but mostly we’d rather not. We often don’t look at the evidence, and we use other people’s opinions when making choices. A lot of people bemoan this “irrationality,” but this is one of the things that makes the human species really amazing; it’s what has helped us conquer the world and get to where we are. I think we are pretty amazing.

Okay, sermon over; there’s another dimension here. The industry assumes that the goal of every consumer’s behavior is to buy something—anything. If we’re working for a marketing organization or a communications company, sure, it is our business goal, but it’s not the goal of the person that we’re researching or trying to sell to. That person’s goals are mostly to get through the day and keep themselves and their loved ones safe, and avoid bad stuff. Sometimes, they have other, more interesting drives, but it’s easy to go too deep, too quickly; who doesn’t like to offer some profound motive for mundane activity? I’m making this example extreme to make the point that, frankly, the models of thinking that I disagree with are often about what matters to the businesspeople who pay researchers and about the stuff they might offer to people, rather than the stuff that people do. In simple communications terms, it’s not what I say as a company that matters; it’s what a consumer does with it and how it resonates in their world, as the late Peter Cooper and Julie Lennon observed.

Zoë: How did you come to these conclusions, despite being deeply enmeshed in the worlds that held these assumptions?

Mark: When I was at Ogilvy, I was working with some amazing strategists from all corners of the earth, most of whom had not been through an Anglophone education in North America or the U.K. They allowed me to see that there was something missing from the conversations we as an industry were having with consumers. If you’ve ever done lots of focus groups, you know that this happens: there’s something below the surface that’s not being said, and your participants are not going to tell you what it is, so you have to find a new way in. Over time, the clues led me to the simple observation that human beings are social creatures, first and foremost. In retrospect—certainly in the age of ubiquitous social media—it’s blindingly obvious that trying to understand humanity by looking at what goes on between our ears (be it with brain scans or by interviewing individuals about themselves) can only reveal a small part of what we’re after. We need techniques that embrace the fact that we are social creatures first and individuals second.

Different cultures have different takes on this. For example, after the apartheid regime collapsed in South Africa, Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu embraced the philosophy of “Ubuntu,” which is mutuality; my success depends on your success. I’m sure you’ve worked in some cultures where this thinking is more prevalent, while in some cultures, it’s every person for themselves. This is really important to know about a culture when we do research there. Most of cognitive science—psychology, and therefore most of the stuff that’s gone into our practice as insights professionals—is based on the individualist Anglo-Saxon way of thinking. It leaves out the idea of mutuality, thus creating a gap in our understanding of how the world and human behavior work.

As I looked further, I discovered there’s a lot of social science which had been making models of human behavior that embrace a bigger picture: particularly anthropology, sociology, network science, and archeology. Archaeologists, for example, have recognized for a very long time that human beings aren’t individuals: they don’t just dig very neat holes in hillsides. They talk about culture—shared views, practices, and behaviors—and they have been creating models of how rituals, practices, language, etc., spread through populations over time, which we, as an industry, just ignored completely because we think it’s just what we do to them that matters. We’re so focused on what the external, exogenous intervention is instead of understanding what deeper and broader influences change their behavior.

Zoë: I see what you mean—it’s presumptuous to think that it’s always an external factor like marketing that impacts individual decision-making when there’s a lot more at play, including a lot of social influences. Following up on that, what are the implications of these realizations that you had for market research and the insights practice at large?

Mark: There are many. Let’s first take sampling. When we draw a sample of, say, 100 individuals, we ask them questions about themselves, their feelings, their behavior, and so on. We then just count heads of individuals claiming to do/feel/say whatever. Which seems fair enough if you are concerned with isolated individuals, hermits, maybe. But this is not how we live, and not how our behavior is shaped. Much of what we should be looking at is the product of interaction between these individuals (or their friends, families, etc.). If we want to understand these products of individuals’ actions within their social networks, we need to sample the social contexts in which individuals act, not just the individuals.

This same insight should challenge the kind of questions we ask of the individuals. When doing research in a category where popularity or word of mouth is the most important factor in decision-making, talking about the product itself is useless. So, we shouldn’t focus on “the thing”—for example, the specs or aesthetic of a phone—but instead focus on the people around the consumer who influence their decision-making about what phone to buy. Instead of asking “What did you like about this phone?” we should be asking questions like “Who did you learn about this from? What did they tell you about it? What other things or rituals have they influenced you on in the past? Why does their opinion matter?” We need to look at the space between them and others, not the space between their ears.

There’s a great paper by Stephen Phillips and Fiona Blades from 2006, which suggests that we should interview a person backwards from the purchase and work out all the influences that happened to that person. It’s an impossible method to do at scale, but strategically, it makes you think very differently about how people actually come to their decisions about what to buy.

Zoë: You said it yourself: though strategically great, this method is impossible to scale. How can we still keep these broader cultural factors in mind when the demands from our stakeholders are to get specific data, usually at scale? Or, to put it more simply: any tips on how to know whether to “talk about the thing” versus talk about everything and everyone surrounding it instead?

Zoë: You said it yourself: though strategically great, this method is impossible to scale. How can we still keep these broader cultural factors in mind when the demands from our stakeholders are to get specific data, usually at scale? Or, to put it more simply: any tips on how to know whether to “talk about the thing” versus talk about everything and everyone surrounding it instead?

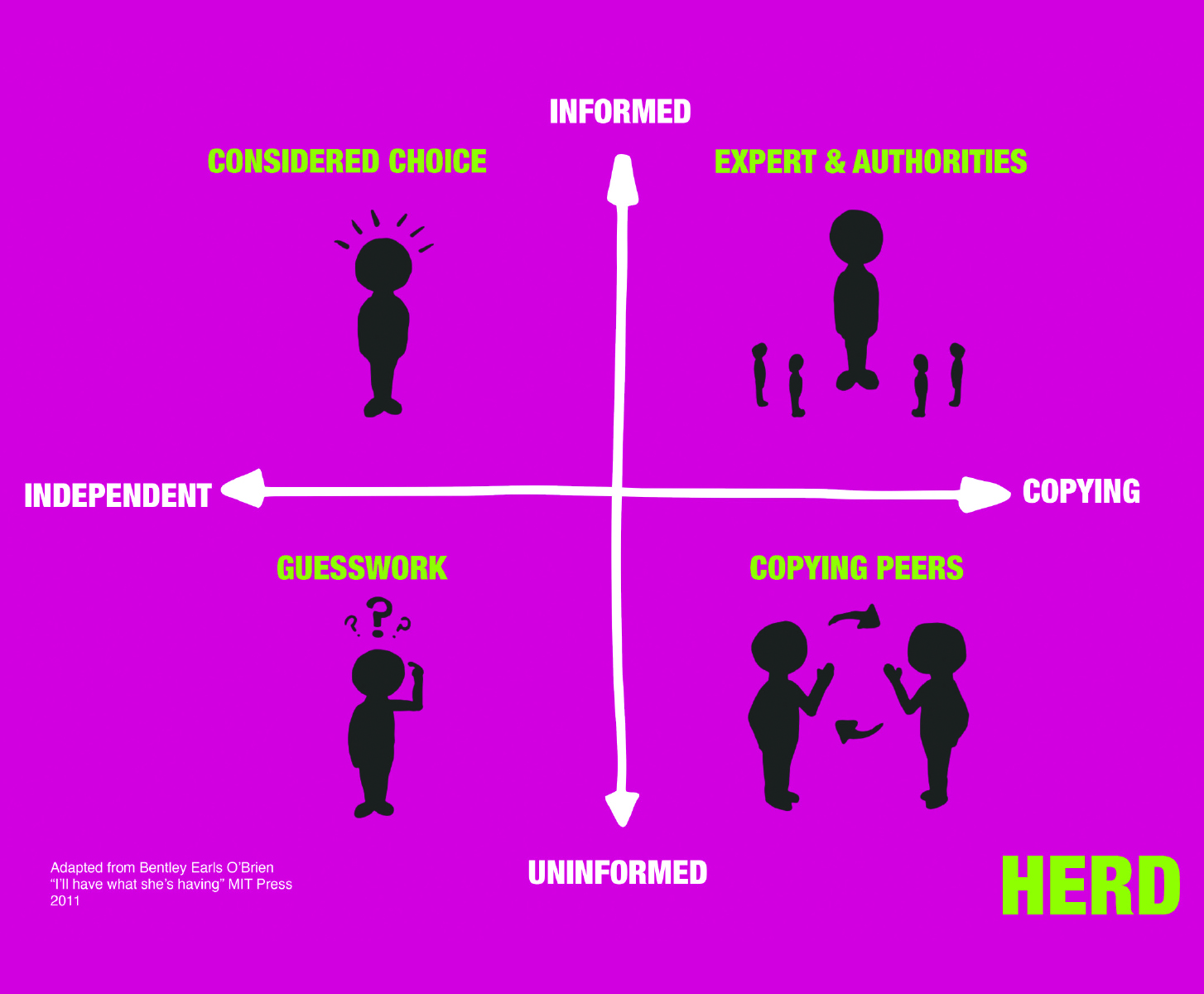

Mark: I worked with Alex Bentley, now a professor at UT Knoxville, on a simple two-by-two map based on patterns in the data that his discipline of evolutionary anthropology has been working on. We used the frameworks and statistical tools of evolutionary science to understand and, therefore, to diagnose what kind of phenomena we’re dealing with. This taught me the great importance of triage rather than precise measurement: understanding types of things rather than specific things. What I mean by this is, when you go into an ER department, there’s somebody triaging you: figuring out what is wrong with you, how serious it is, and what kind of action they need to take. They don’t get precise about the right treatment—that job goes to people like TV’s Dr. House, who gets into the details of how to treat some weird thing that only you’ve got. Too much of the expectation of insights work and market research professionals is to be Dr. House, solving briefs with precision. But I believe there is much more use in being a regular ER insights professional, triaging to find out whether we’re seeing this kind of thing or that kind of thing.

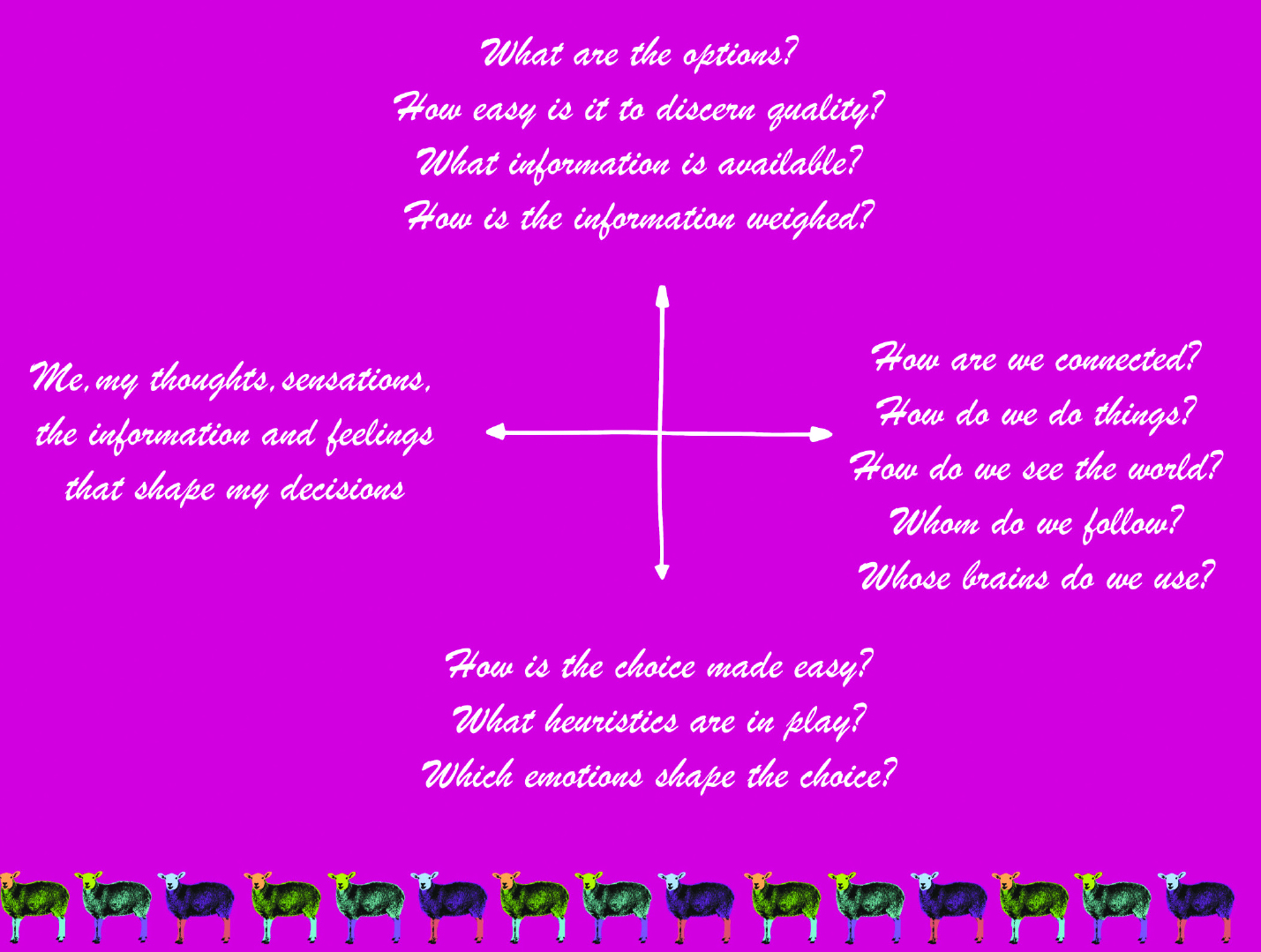

So, this two-by-two map that Alex Bentley and I created is a very simple tool for triaging what kind of behavior or decision we are being faced with—so simple it can be written on a napkin. The x-axis plots independent choice versus social copying. On the y-axis, we look at informed versus uninformed choice.

So, this two-by-two map that Alex Bentley and I created is a very simple tool for triaging what kind of behavior or decision we are being faced with—so simple it can be written on a napkin. The x-axis plots independent choice versus social copying. On the y-axis, we look at informed versus uninformed choice.

Our map is multi-model: it points out four obvious types of choice style based on the distinctive statistical signatures that we observe in behavioral datasets. In the top left quadrant, we have Considered Choices: how most of us tell ourselves and anyone listening that we do things based on wanting superior quality, as if we “consider” the options and the characteristics and benefits available.

Then, in the top right, we have Expert and Authority-led Choices: choices based on recommendations or examples set by others who know about the choice.

In the bottom right, Copying Peers: choices based on what we think is popular or has popular currency at any given time. This changes rapidly as the context around us changes.

Finally, in the bottom left, Guesswork and Habits: choices based on minimal cognitive load. This is what most CPG purchases are based on.

You can do the analysis on your own dataset if you wish. We developed the model by doing repeated analysis, across any number of datasets, commercial and noncommercial, ancient and modern, all around the world, and would recommend a quantitative analysis as an ideal first step. But if you choose, you can just deploy the map as a qualitative triage tool to help orient the category you are studying and place it within a quadrant. Then you can select your research methods and questions that are appropriate for that quadrant. Used in this way, it’s a fast-track to much better research choices. There’s little point in conducting a Freudian deep dive into the decision if you know the category is based on the copying side of the map. It would be far more useful to understand:

- a) What kind of social network the individual is in (is it a tight hub-and-spoke network, with key authority figures acting as models for decision-making? Or, is it a much looser and fluid one, such as we see on Facebook and similar?)

- b) Who do the individuals making the decision look to? How accurately do they model the behavior? How rapidly does the social context change?

Equally, if you discover—as is the case for CPG brands—that habit and repertoire behavior (i.e., repeat and routine purchases) shape the choices in the category, then social listening may not be the most useful research technique, because what are they going to say about something they do every week? If you insist on conducting focus groups on this kind of category, make sure you prioritize the habits and how they are created, reinforced, or changed in your research. Maybe you think recognition on-shelf might be important, so frame your research design around that. Whatever you do, don’t waste your time with brand essences and the like for this kind of category because choices are not that considered.

The same simple two-by-two is also a useful frame to catalog solutions. We examined approximately 150 different successful behavior change case studies, sorted them into the four quadrants, and summarized the classic strategies for each. My book Copy, Copy, Copy: How to Do Smarter Marketing by Using Other People’s Ideas goes into more detail on that.

Zoë: That’s great, I’m jotting the two-by-two down on a sticky note right now! Is there any other advice you want to leave our readers with?

Mark: One thing I would say is this: check your assumptions, your models, and your frameworks. Ours is a discipline—like cognitive psychology I was being rude about earlier—which is the product of a particular culture, time, and place. It’s all too easy to think naturalistically: that somehow our tools are our tools, neutral, and model-independent. Quite the opposite, in my opinion: deep in the heart of much historical practice lies some very Anglo-Saxon ideas about how people are (and how they should be). What if these concepts embedded in our culture aren’t even true of those who grew up in it? Similarly, I’m looking at another cultural idea we take for granted—clock time—and how it has come to squeeze out all the other notions of time in our broader business culture and in research, too. Take nothing at face value!

Mark: One thing I would say is this: check your assumptions, your models, and your frameworks. Ours is a discipline—like cognitive psychology I was being rude about earlier—which is the product of a particular culture, time, and place. It’s all too easy to think naturalistically: that somehow our tools are our tools, neutral, and model-independent. Quite the opposite, in my opinion: deep in the heart of much historical practice lies some very Anglo-Saxon ideas about how people are (and how they should be). What if these concepts embedded in our culture aren’t even true of those who grew up in it? Similarly, I’m looking at another cultural idea we take for granted—clock time—and how it has come to squeeze out all the other notions of time in our broader business culture and in research, too. Take nothing at face value!

Zoë: Thanks, Mark, for giving us lots to think about. Can’t wait to start using your two-by-two in my own research design process!