by Clare Dus, Senior Vice President, Sensory Spectrum, Inc., New Providence, New Jersey, cdus@sensoryspectrum.com and Liz Monroe-Cook, PhD, Monroe-Cook & Associates, Oak Park, Illinois, monroecook@gmail.com

by Clare Dus, Senior Vice President, Sensory Spectrum, Inc., New Providence, New Jersey, cdus@sensoryspectrum.com and Liz Monroe-Cook, PhD, Monroe-Cook & Associates, Oak Park, Illinois, monroecook@gmail.com

Have you ever felt that you were being pulled in two directions as you designed your qualitative research? That you, as the moderator, faced the push-pull of allowing space for the participants to express themselves fully and the desire to answer all the research questions being asked? Have you felt the pressure to give immediate impressions when you know that you want and need the time to review and analyze what has happened in the research process? These are common experiences and tensions for researchers, and this article explores a model that normalizes common tensions, paradoxes, or dilemmas.

The goal of this model, called Polarity Thinking™, as developed by Barry Johnson and others, is to recognize and make the best possible use of universal, normal, and predictable tensions. The Polarity Thinking approach employs “both-and” thinking, incorporates multiple viewpoints, and encourages big-picture thinking at every turn. Polarity Thinking can be applied in a multitude of settings—personal and professional. The focus of this article will be on qualitative research, but we hope that readers will take its applications beyond that focus as well. We have both been practitioners of this kind of thinking for many years and can vouch for its impact and relevance.

So, how does it work? Johnson, noting that the phenomenon of paradoxes was found in philosophy, religion, psychology, science, and multitudes of personal accounts, developed a process and a graphic tool, a polarity map, drawing out people’s tacit understanding of these phenomena. His model encourages people to think about what happens in these dilemmas or polarities:

- How things play out over time,

- What one gains from focusing on one element, and

- How over-focusing on just one side of the dilemma has dire results.

By thinking deliberately through both positive and negative outcomes, individuals and groups can plan actions that make the best use of both sides of a dilemma. Using the model or mapping process helps people avoid making a false choice (misapplied “either-or” thinking) or addressing only one side of a dilemma.

One of the simplest examples of how a polarity works is inhale and exhale. People can immediately see that choosing just one of these would be disastrous for life itself. The ridiculousness of having a “team inhale” versus “team exhale” competition can quickly convey a similar threat that would come from having a “team self-care” and “team care for others” competition, with a “winner” and a “loser.” An important underlying concept, then, is interdependence, i.e., each element needs the other(s) over time.

Johnson and Polarity Thinking practitioners do not argue that we never need either-or thinking. In fact, Johnson often says, “The rejection of either-or thinking is an example of [the overuse of] either-or thinking.” Instead, Polarity Thinking is set forward as a supplemental, although often under-recognized, form of thinking. Knowing when to apply which form of thinking is the key: is it a polarity that will continue to exist, or is it a one-time challenge to solve? The clue that it is a polarity is its ongoing nature, the sense that if we focus on “solving” one side, then we will be forced to address the other side at some future point to avoid dire consequences. A solution to a genuine problem will provide an end point. Polarities never have an end point. “Should we hire Elaine?” calls for a yes or no answer, a problem to solve. “Should we focus on our team or on individuals?” is a false choice because we need to do both.

Another important principle to understand when using this approach is that individuals can and often have preferred poles in a set. Many assessments of working styles might actually address preferences in polarities—for example, focus on the details and focus on the big picture; focus on planning and focus on action; introversion and extroversion. Polarity Thinking can help someone add insights and actions about their nonpreferred pole so that their strengths don’t become liabilities through overuse.

So, before we go any further, we challenge you to think about some of your own preferences. In the following list, circle one item or pole per pair that you feel more drawn to, even a little.

Structure AND Flexibility

Data AND Intuition

Action AND Planning

Humility AND Confidence

Play AND Purpose

Autonomy AND Connection

Being AND Doing

After circling, note which ones were easy to decide and which were difficult. The easier it was to decide, the stronger your preference may be. While it may be more difficult, you now have a good opportunity to strengthen your understanding of the nonpreferred pole through polarity mapping! Noting the strength of your preferences is something you can do as we explore a few polarities here that we think are salient in qualitative research.

Let’s Look at How Polarity Thinking Works

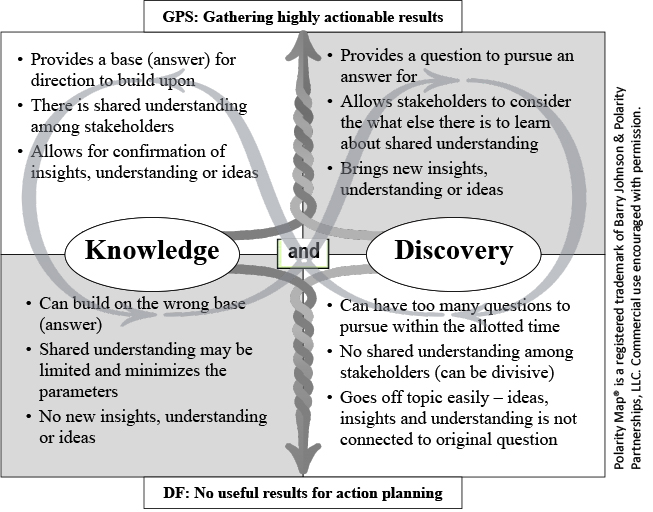

We’re sharing several examples to provide a deeper understanding of how Polarity Thinking works. As we introduce these polarities, you will see them in their map formats with some explanation following each. Some keys to understanding the maps:

- The Greater Purpose Statement (GPS) defines why you are paying attention to and leveraging the best of the polarity or two poles.

- The “upsides” answer the question: What are the positive results of focusing on [this pole]? The “downsides” answer the question: What are the negative results of overfocusing on [this pole] and neglecting the other?

- The Deeper Fear (DF) defines the worst or most threatening outcome for not leveraging the polarity well (ending up in both downsides).

- The infinity loop is the reminder that we cycle through polarities over time (just as with inhale and exhale), and the ideal way to “leverage” a polarity is to spend as much time as possible in the upsides and as little time as possible in the downsides. A short time in the downside serves as the stimulus to move toward the other pole; however, it is not possible to avoid it altogether, just as it’s not possible to avoid the feeling of the essential tension between the poles.

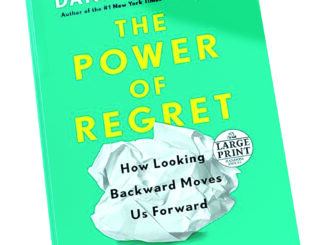

Polarity of BREADTH and DEPTH

Figure 1

The polarity shown in Figure 1 has implications across the stages of your research project. From the times when you are clarifying the purpose of the research, doing your discussion guide, conducting the interviews, and interpreting the results, the question of how much breadth and how much depth will be a constant tension, and rightly so. The old tale about someone looking for their lost keys at night only under the light provided by a street light—“Did you lose them here?” “No, but it’s too dark where I dropped them.”—is the comical version of not having a wide enough lens and doing only what’s immediately obvious. On the other hand (a common phrase when discussing polarities), anyone walking a dog with a specific destination in mind knows it can be difficult to keep the dog going forward, not totally distracted by “pee-mail,” squirrels, or other dogs. Keeping all the possibilities open for information gathering means we might never make it to any objective at all.

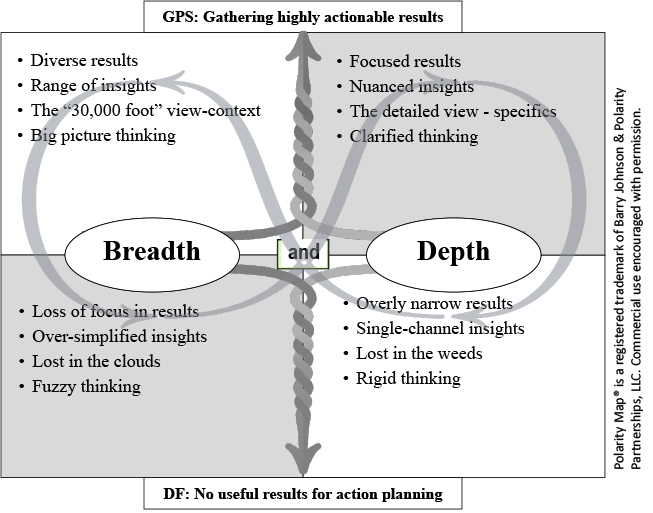

Polarity of THINKING and FEELING

Figure 2

Thinking and feeling may be one of the more obvious polarities when addressing the responses of research participants. In a group, for example, it is often true that people want to appear or believe themselves to have rational reasons for their actions. To discuss their emotions is often more difficult, or the emotions may even be unknown to the persons themselves. Qualitative researchers are pressured to seek underlying motivations, invent ways to get at emotions, and then are left with the task of meaningfully interpreting what it all means. Good luck or long experience with a topic helps.

At other times, the feelings involved for participants are completely obvious, and if you ignore them or remain too much on the thinking pole, you run the risk of looking painfully out of touch with everyone and everything, as in the old joke about a reporter saying, “Other than that, Mrs. Lincoln, how was the play?”

What happens less commonly is an open discussion of the thinking and feeling polarity experienced by the researchers and clients in a project. Yet this tension exists, affecting the research project’s design, communications, backroom experiences, implications, and action plans. This tension may be particularly obvious in projects that have come about because of internal politics, public relations crises, or simply super-sensitive topics either personal or social. While it may be difficult to get everyone to have an open discussion, it is a real advantage to you, the researcher, to be aware of the dynamics as you approach the project.

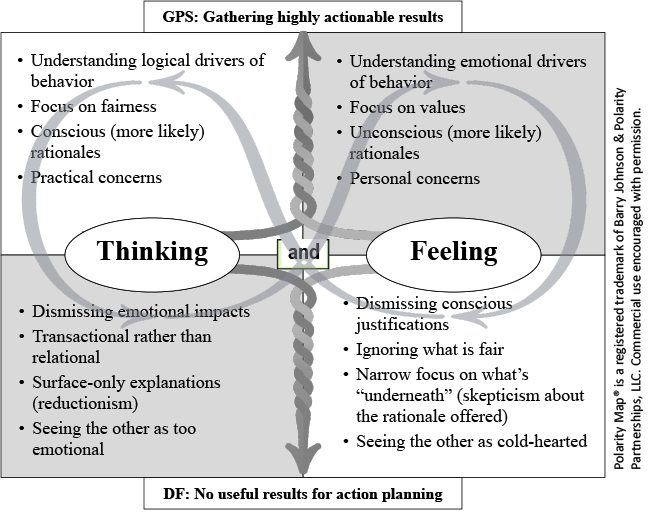

Polarity of STRUCTURE and FLEXIBILITY

Figure 3

All qualitative facilitators wrestle with the ongoing tension highlighted in Figure 3 as they design and execute research. It is inherent in qualitative research and allows for both confirmation of theories, as well as new information for action. As it is impossible for you to talk with everyone of interest in a small amount of time, you leverage, in your research design, both structure and flexibility for optimal results. You apply great care to develop the research structure by determining the number of sessions, length of sessions, number of participants, location, time of day, and the tone of the specific questions, prompts, and activities. At the same time, you build in flexibility for whether or not a participant brings up a topic, as well as time for observer questions. During the session you may also go off script and try alternate questions, stimuli, or exercises from one session to the next. Once the data are collected, you will provide a structured report that allows for flexibility within the discussion and presentation.

Polarity of KNOWLEDGE and DISCOVERY

Figure 4

Frank Herbert’s quote, “The beginning of knowledge is the discovery of something we do not understand,” is captured by this polarity. The need for qualitative research usually begins with the realization that there is a gap in the knowledge concerning the topic at hand. Qualitative researchers take on the roles of explorers to confirm the known and discover the unknown. The flow between knowledge and discovery starts at the very beginning of any research study. All research requires time and money. Building off what is already known allows the focus (and resources) to be on the unknown that will ultimately provide direction for action planning. This polarity also shows itself in your facilitation approach as you encourage, with an attitude of curiosity and naivete, the participants to share of themselves.

Applying the Polarity Map with Consumers

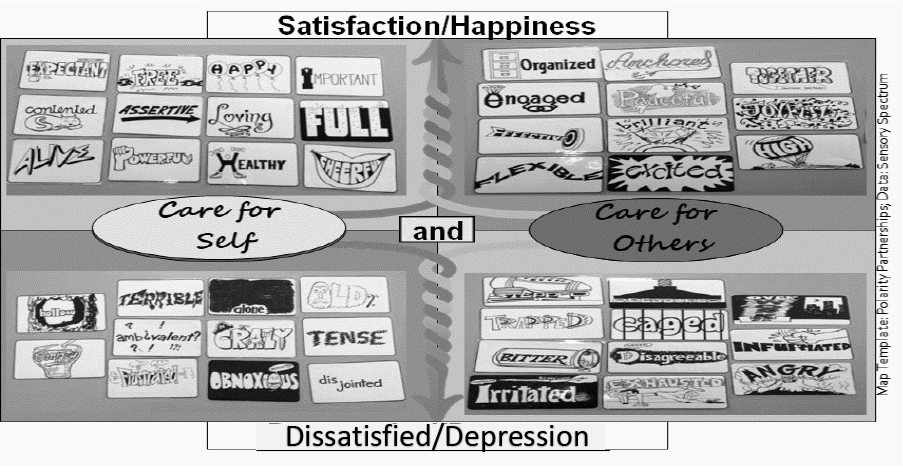

Exploring CARE FOR SELF and CARE FOR OTHERS

Figure 5

As polarities are part of the human experience, they can be explored with participants for further understanding. Sensory spectrum researchers use polarity maps to understand the competing tensions that people face when making purchasing decisions. In one exercise, with emotion cards (by ERI Press, though now discontinued), participants were asked about the push-pull they experienced as they grocery shopped for themselves (care for self) and their family (care for others). The use of the polarity map allowed the participants to bring depth to their experience story. Notice the diversity of emotions expressed when participants experienced both the upside of a pole, as well as when they experienced the downside or overfocus of a pole.

This latter example shows the broad scope of applications of the polarity idea. It is a tool for your own thinking, a tool for working with your clients, a tool for planning and analysis, and a tool for enlarging the exploration with your research participants.

Polarity Thinking for Action Planning

While the length of this article doesn’t allow us to explore it, please know that this approach is not only great for analysis of a situation, but also for action planning. The full map of a polarity includes looking at:

- Action Steps—the specific things that will help you to “… gain or maintain the positive results from focusing on this pole”; and

- Early Warnings—the first indicators “… that will let you know that you are getting into the downside of this pole.” You can learn in depth about Polarity Thinking and the mapping process from Barry Johnson’s book, AND: Making a Difference by Leveraging Polarity, Paradox, or Dilemma; Volume One: Foundations (HRD Press, Amherst, MA 2020).

The best way to begin using Polarity Thinking yourself is to fill out maps for some common polarities, or ones that may help you get unstuck from overfocusing on one pole. A short list of possibilities follows on which you can practice, beyond those we already have included. You may also find yourself discovering polarities as you begin to ask yourself, “Is there a ‘both-and’ here?” We are surrounded by them.

Key tips as you begin to list polarities you discover: avoid expressing a preference; be sure to keep the names of the poles either equally neutral or equally positive, for example, activity and rest, not activity and laziness.

Complexity AND Simplicity

General AND Specific

Actual AND Perceived

Cost AND Quality

Lead the Market AND Respond to the Market

Qualitative AND Quantitative

Experiencing AND Observing

Speedy decisions AND Mindful decisions

As we stated at the beginning, we have both benefited greatly in our work by using this approach. Furthermore, it is our experience that research-minded folks are particularly adept at addressing complexity intuitively and explicitly. We hope that Polarity Thinking will be another important aspect of your worldview and part of your research tool kit. It is a deliberate way to exemplify the F. Scott Fitzgerald quote found in a lot of descriptions of polarity and paradox: “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.”