By Chris Kann

Owner and Principal

CSK Marketing, Inc.

In the qualitative research industry, and especially among moderators, “laddering” is a common and well-known technique for asking questions during an in-depth interview. Though it is a foundational skill, the technique can be misunderstood as a rigid process rather than a flexible interviewing option. So, laddering deserves a closer look, whether you are just starting out in your qualitative research journey or are well along the path.

In the qualitative research industry, and especially among moderators, “laddering” is a common and well-known technique for asking questions during an in-depth interview. Though it is a foundational skill, the technique can be misunderstood as a rigid process rather than a flexible interviewing option. So, laddering deserves a closer look, whether you are just starting out in your qualitative research journey or are well along the path.

I don’t officially remember where or when I learned about laddering, but if I’m honest, I haven’t always enjoyed laddering as a process of asking questions. I have sometimes found it limiting and even irritating—for me and the respondent. My frustration led me to spend time thinking about why I found laddering to be a little contrived and unnatural, and how I could approach it in a way that made more sense for me, and made it feel more respondent-focused.

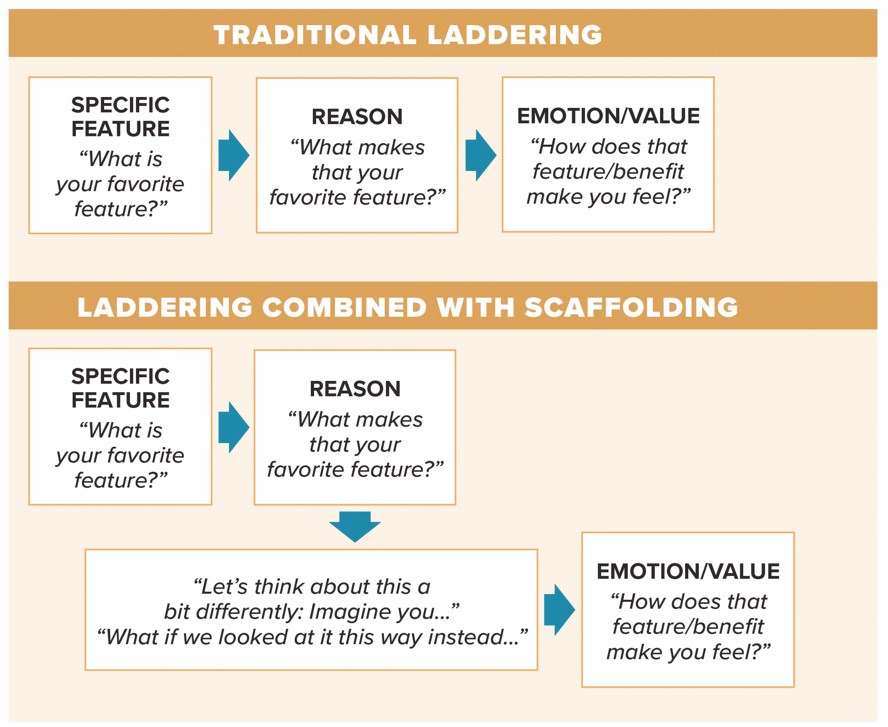

Laddering is a qualitative interviewing technique that aims to uncover the underlying motivations and values driving a respondent’s choices, behaviors, or perceptions by asking a series of questions. The researcher moves from concrete attributes of a product or service to more abstract personal values, allowing researchers to gain a deeper understanding of the respondent and the decisions they make.

The technique is used to go beyond the conscious and to invite and encourage self-analysis of behavior and the associated motivation. Most respondents have not thought deeply about the reasons behind their choices. For them, to be with a researcher, being asked to explore and explain their thoughts and choices, can be a very new experience. When done well, laddering can help bring great insight and self-awareness to a respondent, and it is worth understanding more thoroughly.

The ultimate objective of laddering is to gain an understanding of values, emotions, and beliefs that the respondent indicates are part of their decision-making. For example, imagine a researcher wanting to know how their respondents are connecting to the type of pen they use and why they bought that brand or model. They would begin the laddering phase of the interview by having respondents identify something specific about the pen so the researcher can gain insight into what is most important to the respondent. That might be stated as: “What is your favorite feature?” or “What is your favorite part of that experience?” Let’s say in the pen example, they indicate their favorite feature is that the pen does not smear when they write. Once they’ve identified that feature, the researcher can start to explore some of their reasoning.

The next question should stay focused on that feature and explore what makes that the favorite or most important feature, or the respondent’s favorite part of an experience. If the first reason they iterate is not quite as reflective as you are hoping, the researcher could iterate on this to dig a bit deeper, by saying, for example, “And what else makes that your favorite feature?” This allows the researcher to uncover additional insights and what seems most worth exploring toward the research objectives.

The respondent might say that the feature is most important because they don’t want to get ink on their hands. The researcher then wants to turn the conversation toward identifying the emotions or beliefs that are linked to that feature. So, for the pen example, the researcher might ask, “How does it make you feel when your pen does not smear?” or “Let’s say you just took notes in a meeting and your pen did not smear . . . how do you feel?” They might say “they feel relieved and less stressed that they don’t have ink on their hands” or that “they avoided the embarrassment of having their pen leak at work.” In a quick and efficient way, the researcher now knows that the respondent chooses to buy this pen because they can count on it not to smear, and this prevents them from being stressed and embarrassed at work.

Laddering Key Words and Phrasing

As much as possible, researchers want to avoid using the word “why” to lead questions. Focus instead on “what” and “how.” Asking “why” can seem as if you are questioning or judging the respondent’s behavior or decisions, when, in fact, the researcher is just trying to understand them. Consider these two choices of questions:

- “Why do you always shop at the same grocery store?”

- “What about that grocery store makes it your preferred choice?”

Can you see how the first phrasing might sound like the moderator is judging a respondent’s decision-making rather than seeking to understand it? For this reason, I do not recommend the “Five Whys” technique that is sometimes mentioned in discussions about laddering. That approach was developed by Sakichi Toyoda, the founder of Toyota Industries, as a way to understand quality control issues within Toyota Motor Corporation. In this interviewing style, a respondent is asked “why” five times to ascertain an understanding. But, as you can imagine, this could make the questions sound more like those of a petulant toddler than a research interview seeking to understand. This approach could cause a respondent to rightfully shut down or get defensive, which is not what we are seeking to accomplish when we are instead looking to understand more complex and dynamic things like emotions and values.

Be Respondent-Focused for More Effective Laddering

When you do more comprehensive laddering, don’t lose track of your interaction with the respondent. Don’t become so intent on the end goal that you develop tunnel vision and miss clues that the respondent is feeling frustrated or that something else was said that invites you to dig a bit deeper for an unexpected insight.

It can be very easy to be so focused on the sequencing of the questions and miss that the respondent is struggling with articulating their thoughts or has hit a dead end. In those instances, you need to be prepared to pause, shift, rephrase, and do what you can to get the interview back on track. You don’t want to overwhelm a respondent or lose them because they have stopped being able to respond to your questions.

This could be a very new, uncomfortable, and unfamiliar experience for a respondent to think deeply about a product or service, what is important, and how they feel. They may not necessarily be able to find the words for what they are experiencing, so be prepared to potentially rephrase or take a bit of extra time for a response. The longer you go in an interview, respondents can simply become less accurate because they just aren’t sure, they are frustrated, they aren’t willing to share, or they are fatigued. Pay attention—observe your respondent—and be cognizant of the emotional cues your respondent is displaying.

Budget Time for Laddering and Accompanying Analysis

If you are striving to do more in-depth or broad exploration, this can take a good bit of time, so make sure that you have built that into your guide. By giving observers advance notice that this process needs to proceed at a pace that allows for reflection, they can anticipate concerns about time usage.

Because each interview could be very different, the analysis of laddering data can be more challenging. Responses might not be consistent; therefore, it can be more difficult and complex to analyze. Plan for a more multifaceted approach to analysis that could be less linear than a standard interview.

Scaffolding: When Laddering Does Not Seem to Be Flowing

In cases where a respondent is getting stuck on the questions, there could be an opportunity to consider adding a technique called “scaffolding” into the mix. Scaffolding is a process of asking and progressively building on questions to guide respondents toward understanding, providing support and guidance as the respondent gradually gains the confidence required to answer.

The foundation of scaffolding lies in education, and the technique is meant to ensure that a student understands a concept before moving to the next stage of learning. This involves a supportive approach to questioning, making sure that the respondent is fully understanding the questions before you move on. The interviewer remains flexible; so, if you feel the respondent is not quite understanding the questions, you can rephrase or give them more time. This approach can then feel more like an interactive dialogue than what they might be perceiving as an interrogation.

The key to using scaffolding to shift the interview and allow the respondent to get back on track is to change the perspective that the respondent is viewing the questions from. Rather than continuing a linear path, be open to taking a side-step and moving laterally to a question that can allow them to reset their thinking. For example, if a question like “What about that grocery store makes it your favorite?” has them struggling for an answer, a follow-up question could be: “Let’s think about this a bit differently. Imagine you were moving into a new neighborhood; what would you be looking for in a grocery store that could make it your new go-to choice? What else? What about those qualities made them jump to the top of the list for you?”

The key to using scaffolding to shift the interview and allow the respondent to get back on track is to change the perspective that the respondent is viewing the questions from. Rather than continuing a linear path, be open to taking a side-step and moving laterally to a question that can allow them to reset their thinking. For example, if a question like “What about that grocery store makes it your favorite?” has them struggling for an answer, a follow-up question could be: “Let’s think about this a bit differently. Imagine you were moving into a new neighborhood; what would you be looking for in a grocery store that could make it your new go-to choice? What else? What about those qualities made them jump to the top of the list for you?”

After asking a question that helps change perspective, you can then return to the laddering questions to complete the interview in a similar place as if scaffolding had not been used. But these “perspective pivots” that scaffolding questions can offer will ensure the interview gets completed.

The researcher can now be most focused on making sure the respondent is self-reflecting and revealing insights than if there is a clear linear or hierarchical track of questions being followed. A respondent who is carefully guided through questions of self-reflection will provide what is needed to understand their decision-making process and emotions, even if the questions stray slightly from the originally intended wording. This provides a far better chance that you don’t lose a respondent who becomes confused or overwhelmed by the laddering questions.

With this rephrase or pivot in perspective, the respondent can think about the question differently and refresh their response in a way that would shift their thinking and cause them to see their priorities and preferences in a new way. You still identify the things that are most important about a grocery store, for example, but from a different perspective. A scaffolding question asks a respondent to imagine themselves in a new space, or to view a question from a new angle. This creates a break from the linear nature of the laddering questions that can allow the interview to move forward rather than stalling.

The ideal combination of the linear or hierarchical approach of laddering with the responsiveness and support of scaffolding creates options that have helped my interviews feel more natural with a smoother flow. A discussion with a respondent then becomes more focused on their thorough participation rather than simply the predetermined questions on the page.

Compared to the linear process of laddering, scaffolding is meant to be built as you go, moving horizontally and vertically in ever-deepening insight, also toward a goal of understanding. The scaffolding approach allows for more flexibility to move sideways with your questions in a way that can adjust to different respondents and what is needed to take that respondent to deeper self-reflection. The same questions don’t always work for each respondent, and this addition of scaffolding reflects that.

Laddering and scaffolding are similar, different, as well as complementary. I recommend you have both approaches in mind during interviews where you are leading a respondent through self-reflection, especially when an interview is not flowing smoothly. I believe it will allow you to gain more from your interviews to have this flexibility.

Using laddering and scaffolding does become more natural with practice. You don’t need to be in a formal interview situation to do laddering; you can experiment with family, friends, and even strangers. Just don’t try it on a 4-year-old to find out about their day at school. I tried it and would not recommend it!