By Zoë Billington

UX Research & Customer Insights

Los Angeles, California

zbillington@gmail.com

This quarter, I spoke with Samara Bay. Samara is the author of Permission to Speak, an invitation to reimagine what power sounds like. It is available in 15-plus countries and five languages, and is a number-one bestseller in Women & Business and Public Speaking. She leads Permission Inc., a global consultancy where leaders become brilliant speakers. Based in Los Angeles, Samara supports celebrity clients, political powerhouses, executives, and educators on their leadership and speaking engagements. Samara’s work has been featured in TIME, The New York Times Magazine, Forbes, Glamour, Vanity Fair, Fast Company, Entrepreneur, and on CBS Sunday Morning, Deepak Chopra, and NPR. She’s a professor of practice at USC’s Annenberg School of Communication and Journalism.

This quarter, I spoke with Samara Bay. Samara is the author of Permission to Speak, an invitation to reimagine what power sounds like. It is available in 15-plus countries and five languages, and is a number-one bestseller in Women & Business and Public Speaking. She leads Permission Inc., a global consultancy where leaders become brilliant speakers. Based in Los Angeles, Samara supports celebrity clients, political powerhouses, executives, and educators on their leadership and speaking engagements. Samara’s work has been featured in TIME, The New York Times Magazine, Forbes, Glamour, Vanity Fair, Fast Company, Entrepreneur, and on CBS Sunday Morning, Deepak Chopra, and NPR. She’s a professor of practice at USC’s Annenberg School of Communication and Journalism.

Zoë Billington: Let’s start as we always do with the 10,000-foot view of your career. How do you tell the story of your career and how you got to where you are today?

Samara Bay: When I was around 10 years old, I was determined to be a Shakespearean actress, but after getting my MFA in acting and doing the New York theater thing, I kept getting drawn toward dialect coaching. Still in the realm of the arts, but from a linguistic perspective, designing with my actors the story of a character’s voice. I did this first in New York, off Broadway, and on Broadway, and then in Los Angeles, working on TV and film sets.

As I like to say, I have a long history of telling movie stars what to do with their tongues. But the truth is, the job was always more interesting than that. I was often coaching folks for whom English was their second language, in environments where they needed a safe space to unpack their own voice and their own relationship to their voice. Then, when they would get the chance to give a speech as themselves at the United Nations or an award show, they would turn to me and we would do that work, and it would feel the same but different because now the role they were playing was even harder: themself.

Fast forward to the summer of 2018. I was coaching Gal Gadot on the Wonder Woman sequel. I was in Washington, D.C., for the summer, and we were in a heated political moment. I was trying to go to as many protests as I could and write postcards, but I was feeling generally pretty useless until I got a call from MoveOn.org, a great group that, among other things, identifies great first-time candidates for office and then gives them resources. They needed folks to jump in pro bono and coach all these women on their stump speeches—this was the blue wave, before we knew there would be a blue wave. I dove in, and it totally changed my life. Here were all these brilliant women whose life experiences—as caregivers, community members, employees—meant that they might actually represent us. They were the leaders we were looking for, but every single one of them had trouble translating just how brilliant they were through the microphone.

As I was coaching them, I was struck by the fact that this is not a person-to-person challenge. This is a cultural challenge. There’s a whole collective story about public speaking—who tends to take the floor, what they tend to sound like, and what cues authority—that is ripe for a rethink.

From there, I ended up pitching a podcast on the subject of women and voices and power that sold to iHeart Radio, and a book that sold to Penguin Random House, and I now exclusively speak about and support leaders in showing up in a fresh way when they speak.

Zoë: Can you talk more about what you mean when you say there’s a “story” about public speaking that needs to be rethought? How is that different from this new, fresh way of speaking that you’re helping leaders discover?

Samara: Well, I think we can probably all build the story together. There’s the belief that your voice should be low-pitched, not high. You should go down at the end of your sentences, not up. No apologies, no ums, no unnecessary use of the word “like.” Speak at a measured pace, so you sound like you’re at 75 percent of your natural speed of speech, and speak with a lot of emphasis, so you make sure people know you mean business. If you Google, “How do I sound more authoritative?” Google will—and this is even before AI took over—spit out five bullet points, packaging how to sound more authoritative. Truly, it’s everything you could guess: one of them is something about physical confidence, like puffing out your chest. The other four are vocal, like those I just mentioned. Another one I’ll add, because it just lives rent-free in most of our shared consciousness, is: don’t be emotional. The shorthand for “Don’t be emotional” is don’t cry, but even seeming enthusiastic is discounted as risky for credibility.

So, the question is, in what ways are these stories useful? Or not? What’s the evidence all around us of people showing up deeply human, following none of those rules, and making an impact anyway? You might ask yourself, who’s the last person that you felt the physical urge to forward online once you watched their speech—and does that person sound like what Google would say an authority figure is supposed to sound like . . . or are they pointing us to something fresher?

So, the question is, in what ways are these stories useful? Or not? What’s the evidence all around us of people showing up deeply human, following none of those rules, and making an impact anyway? You might ask yourself, who’s the last person that you felt the physical urge to forward online once you watched their speech—and does that person sound like what Google would say an authority figure is supposed to sound like . . . or are they pointing us to something fresher?

My clients and I have found that the old sound of power has resulted in, frankly, a lot of boring speeches and a lot of leadership that doesn’t work. Meanwhile, there’s a burgeoning new sound of power we see once we look. U.S. Congresswoman Jasmine Crockett comes to mind. As we record this, she was just asked on the steps of Congress if she had any words for Elon Musk, and she gave a very short and curse-y response that felt true to her and true to the moment—what we might call authentic. I’m not saying you have to use curse words to signal authenticity, but I do want to challenge you to consider: what if the way you show up around your favorite people, around whom you have nothing to prove, is instructive? A place to explore how honest—and how honest about your own style of speech—you can be in public? What if those moments point each of us to a new sound of power? From there, we can begin to build out our sense of permission. So, when we have the chance to share our pitch, our idea, and stand on our own conviction, we think to ourselves, uh oh, I don’t sound right, we can move past those old standards. For many of us, we are the first generation to speak on our own conviction in public, and attempt to do so unapologetically, despite the stigma of generations silenced or shaped into an unrecognizable form.

Ultimately, we need to get away from the idea that it’s a zero-sum game—that you can either be authentically you, or you can keep your job—and move to something that’s truer: when we show up with a twinkle in our eye, the belief that our idea is really good, and curiosity about what our audience needs, we show up human, we sound like ourselves at our most free, we make the impact, and we get the “Yes.” This isn’t just feel-good; it’s strategic. It’s what works.

Zoë: How can we start chipping away at these outdated stories about public speaking and create a new sound of power?

Samara: So, I talked about the external “story” we’ve all been told culturally, but each of us also has an internal voice story. You may have heard people use terms like a “money story” or “body story” to capture the essence of the narratives we each hold onto about money or about our bodies that we picked up unintentionally. For voices too: each one of us has a collection of truths, of half-truths, and of myths we’ve been gathering our entire life about how we sound, how the world perceives us based on how we talk, and how powerful people sound and should sound.

Maybe your family always said you were too loud. Or the kid in high school made fun of your laugh. Maybe it’s the accent that you know was different from your classmates, or the advice you got at your first job to stop saying “like” too much if you ever wanted to get taken seriously. For all of us, it’s a combination of the things that happened to us and the things we did—the way we were raised, when and why we left, who we were hoping to become, and who we’ve spent time with. This is rooted in sociolinguistics, a field that says the voice each of us has is because of the life we’ve lived and all the micro-adjustments we’ve made based on the feedback we’ve gotten. Too this, not enough this.

So, here we are with the voices we have, and the stories we’ve collected. I’m not good at public speaking, or my voice is annoying, or my laugh is too loud. Part of the process of supporting folks with their public speaking opportunities often involves helping them see how much of their voice story is actually a narrative that’s due for a rewrite, a story whose time is up. Like, hey, that bully in second grade who said that mean thing? Does that need to impact the way you show up now in your 30s, walking into a room of power? Is that serving you? If not, what’s a more generative thought process?

Zoë: Can you share an aspect of your own voice story and how unpacking that story has impacted you as a public speaker?

Samara: In my early 20s, I lost my voice for many months, and I wasn’t sick. I was in the middle of my graduate acting program, so I was talking all day and singing all day, and it became increasingly more painful to speak until I finally just stopped. I was going to class anyway, because you can’t not go to class just because you don’t have a voice, but my throat was screaming at me whenever I’d utter a word, and late nights in the dead of winter in Providence, Rhode Island, I’d sip tea with honey, managing an existential crisis. Wondering, what is happening? What is my voice trying to tell me? I finally got myself to an ear, nose, and throat doctor, and they stuck a tiny camera up my nose and down the back of my throat. It’s quite a feeling. I got a photo of my vocal cords, and it was obvious because there was a blister in the same exact point on both sides of the V—I had vocal nodules. I got back to class that day, and in front of everyone, the gentleman who ran the program stopped everything and said, “So what’s the diagnosis?” I replied, as audibly as I possibly could through the pain: “Vocal nodules. I have to go on full vocal rest for a month and a half.” He said, “Yeah, just as I thought, bad usage.” He was saying: You did this to yourself. You’re not just the injured party here, you’re also the perpetrator—for shame.

Although the timing worked out for me to take those six weeks of silence back in my hometown during winter break and go to a speech pathologist and relearn how to talk, processing his comment actually took much longer because he was right on some level; there was some usage issue. But why would I have picked up a habit that would ultimately self-sabotage myself? Why would any of us pick up any vocal habit that would sabotage ourselves? This is where this idea of voice story and voice biases is really useful to remind ourselves what sociolinguists already know—imagine them cheering us on from the sidelines—that every habit any of us has picked up, we’ve picked up for a reason. It has served us in some way—to do something that felt like survival or safety or success. The question now is, what about now?

As for me and those vocal nodules . . . turns out, I had been habitually speaking a tiny bit below my body’s optimum pitch. Why would I have picked up a habit of talking a little bit lower than my body’s optimum pitch? I don’t know. Should we Google it? It’s ultimately so obvious, but in my early 20s, I didn’t know I’d been picking up what society was putting down and needed a whole new story; so, I stopped trying to chase a standard that wasn’t made for me. That wasn’t made for most of us.

Zoë: What a story and a great example of how uncovering your own voice story can be transformative to not just your career but to your quality of life more broadly. Applying this to a context that is perhaps more familiar to our readers, a lot of what we do as researchers is tell stories using consumer data to influence business decisions. That data can, in a way, be seen as the consumers’ voice, not our own. What role do you think our personal voice plays in our ability to influence others?

Samara: From what you’ve told me, it sounds like your industry has undergone some major shifts, first in positioning yourselves as consultants rather than data suppliers and now figuring out how to position yourselves in the age of artificial intelligence (AI). As AI becomes more powerful, it’s even more important that we claim our humanity inside of the data: not just the humanity of the folks that the data was collected from, but the humanity of those who are interpreting it. Meaning that, yes, if you’re wondering if you should have a point of view, you should. Your point of view is not based on random opinion, but rather, that you feel strongly because the data tells you so. You’re allowed to care about it—you don’t need to remove yourself from it or act detached in order to uphold old standards of “credibility.” So, in this moment, when researchers are reconsidering their identity, I’d love to offer you permission to care. Care does not mean bias. It doesn’t mean that you’re introducing something nonscientific into the science. It means that you’re passionate about getting to the truth of the thing. I say this as the daughter of an astrophysicist. I grew up going to physics conferences all over the world. Science is something I respect deeply, but I also know its culture can be a trap. We must not equate credibility with detachment. We must allow our excitement over our work, over discovery, over clear data, to be part of how we communicate the work.

Zoë: For readers who have a big presentation coming up, a difficult conversation ahead of them, or perhaps are getting ready for a pitch, what are some tips for how they can prepare themselves to show up with this care and authenticity you speak of?

Zoë: For readers who have a big presentation coming up, a difficult conversation ahead of them, or perhaps are getting ready for a pitch, what are some tips for how they can prepare themselves to show up with this care and authenticity you speak of?

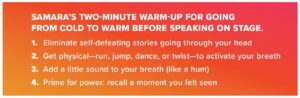

Samara: I wrote Permission to Speak for when folks find themselves exactly in this scenario. It’s welcoming and warm and offers a bit of breath and space so each reader can find their own door into this old-fashioned world of “public speaking.” But for something you can start doing immediately, I like to offer a warm-up before stepping on stage or turning on a camera or a microphone. The concept of a warm-up feels like the sort of thing that an actor or an opera singer might do, which can alienate people. So let me just lovingly suggest that you use your two minutes before stepping out on a stage to go from cold to warm. What might you do in those two minutes? I have four ideas. Do all, do none.

The first suggestion is to notice if there are any stories going through your head that are going to get in the way of you really showing up on that stage. If you’re standing behind the curtain thinking, I hope they don’t think I’m terrible at this. I hope I don’t mess it all up; those stories are not going to help you. An MRI scan would show that those thoughts trigger a somewhat debilitating chemical response. Rather, if you notice any old stories coming up, offer that voice inside your head: Thank you, I’m good. Thank you for trying to protect me, but I don’t need you here now.

Suggestion two is to get a little physical. For as long as there have been orators, there have been suggestions to move your body. Run around the block, do jumping jacks, dance, bend over and slowly roll up, twist so that you awaken your spine. The reality is your body holds a huge amount of wisdom. It can read rooms and adjust accordingly. It can breathe deeply enough to connect your thoughts to your spirit to your voice, so you have a shot at really showing up, but you do have to invite it in.

The third suggestion is to add a little sound to that breath. Even just a hum up and down your range is enough so that when you walk out on the stage or you press go on that camera, your voice is not foreign to you. You have heard yourself. You know what you sound like today.

The fourth and final suggestion, if you have time for nothing else, is called priming for power among psychologists. Bring to mind a time when you felt really seen. You can collect these in advance to have a few at the ready. Maybe someone you admire admired you back. Maybe you got a text or an email or a hug, or you heard through the grapevine that your contribution really mattered. Bring to mind that memory. Breathe it in with your whole body, let your body feel the memory, and it will prime you for the kind of power—meaning power to agency—that you have inside of you already, and when you walk out on that stage, that version of you will show up.

Zoë: Before we wrap up, is there any other advice you’d like to offer our readers?

Samara: Toni Morrison once said, “As you enter positions of trust and power, dream a little before you think.” My dream is that we feel alignment, connection, and sparks of delight when it comes to our chances to speak in public, so that our ideas on the inside become things on the outside—real and beloved. If our whole history of public speaking leaves us with a sense of fear, then the opposite of fear is love. What would an approach to public speaking that’s love-based actually mean for you, for me, for us, for our kids, and for the world?

Zoë: That’s a great provocation to end on. Thanks so much, Samara!