By Laura Quinn, BS, MBA

President

PJ Quinn, Inc.

Azle, Texas

laura@pjquinninc.com

Marketing researchers often navigate deeply personal and emotionally charged research topics. However, few topics are as sensitive and challenging as those involving individuals living with chronic or life-threatening illnesses. These participants bring unique personal perspectives of their journey with a life-threatening disease, particularly with respect to treatment and unmet medical needs. Drawing from recent emotional insights studies conducted by PJ Quinn, Inc., this article offers practical strategies for conducting emotional insights research with seriously ill patients. By blending rigorous methodology with compassionate engagement, we can amplify their voices, deliver actionable insights for pharmaceutical and healthcare clients, and honor their lived experiences.

The Value of Emotional Insights

Emotional insights reveal the human impact of illness: how it affects daily life, how treatments are perceived, and where gaps in care persist. For healthcare stakeholders, these insights provide a window into the patient’s voice that quantitative data alone cannot capture. The insight gained from qualitative research informs product development, patient support strategies, promotional communications, and improved care delivery. However, eliciting these insights requires a thoughtful, empathetic approach, as participants may grapple with fear, vulnerability, or exhaustion during interviews. The challenge for researchers is to delicately balance business objectives: avoid unduly upsetting participants and ensure robust findings without compromising empathy.

Preparing for Success

Research success begins before the first question is asked. Recruiting seriously ill patients is challenging, time-intensive, and often costly, requiring collaboration with multiple recruiters or patient advocacy groups. This necessitates a doubling of the recruitment effort compared with typical studies with healthcare professionals. Clients must be prepared for this reality and understand that flexibility is essential due to participants’ varying understanding of medical vocabulary and emotional resilience.

Key Preparatory Steps Include:

Set Clear Expectations in the Screening Process

- Be upfront with participants about the study’s purpose, duration, and limitations.

- Avoid inadvertently raising false hope (e.g., implying a cure).

- Ensure participants do not expect personal benefits from hypothetical treatments shown in research stimuli.

Prioritize Empathy

- Build in warm-up and cool-down periods to ease participants into and out of discussions.

- Be ready to adapt or back off if emotions run high.

Minimize Distractions

- Keep sessions concise and focused—time is precious for these individuals.

- During telephone or webcam interviews, employ technical safeguards like monitoring mute settings to prevent unintended disruptions (e.g., a listener’s casual, accidentally unmuted remark can be disastrous during a sensitive discussion).

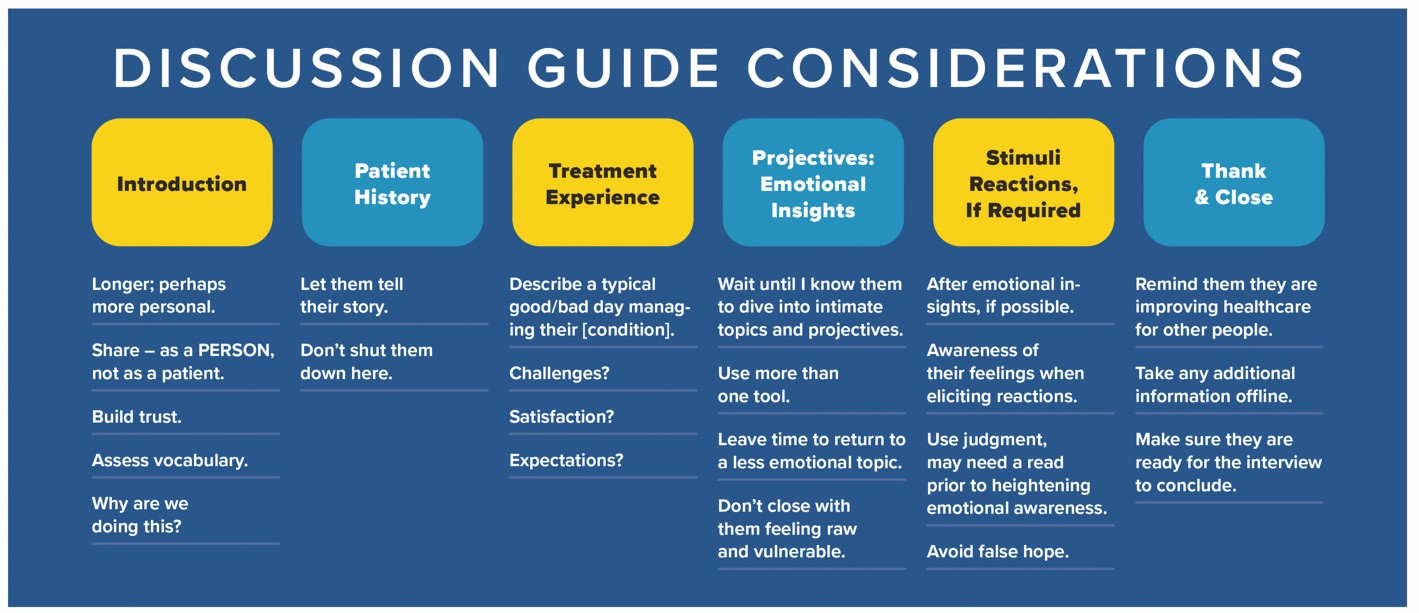

Crafting the Discussion Guide: Balancing Needs with Projectives

A well-structured discussion guide balances client objectives with respect for participant comfort—it’s tempting for rare diseases, especially, to run long. But guides should be concise, leaving room for projective techniques and required adverse event reporting, if necessary. This ensures interview efficiency without overwhelming participants.

Start Personal, Not Clinical

- Open with an extended, trust-building introduction that invites participants to share as people, not just patients. This helps assess vocabulary and tailor language.

- Help to relax the participant by the moderator sharing a little information about themselves.

Let Their Story Unfold

- Allow uninterrupted time for patient history and treatment experiences to foster engagement before exploring deeper emotions.

- Avoid the temptation to abbreviate this story. Time well-invested here pays dividends later in the interview when helping the participant let their guard down for projective exercises.

Introduce Projectives Thoughtfully

- Use indirect methods like storytelling or visual exercises after rapport is established.

- Employ techniques such as the “Magic Wand” (“What would you change about your treatment?”) or “Blob Tree©” (selecting characters to reflect feelings) to unlock emotional depth.

- Follow with neutral topics to avoid leaving participants feeling raw at the close of the interview. For example, one might turn to something less emotional, like asking the participant to describe what information sources they use to learn about the condition they live with.

Close with Purpose

- Remind participants that their input improves healthcare for others, and check that they’re ready to end, ensuring emotional stability.

Sample Projective Techniques in Action

When presenting stimuli, gauge emotional readiness and reinforce transparency about their relevance to the participant’s situation. Using multiple projective techniques accommodates diverse personalities, enhances comfort, and strengthens data reliability by triangulating findings. Projectives elicit nuanced insights without forcing direct confrontation of difficult emotions.

Examples we’ve used with success include:

- Magic Wand: “If you could improve any one thing about your medication regimen, what would it be?” or, “If you could change one thing about the way your healthcare team manages your condition, what would you focus on?” This technique invites practical yet aspirational responses.

- Blob Tree©: “Which character reminds you most of how you feel living with your condition? What in that image reflects your thoughts?” This visual tool sparks nonlinear thinking. (www.blobtree.com)

- Letter to Younger Self: “Imagine you could write a letter to your younger self. The purpose of the letter would be to tell your younger self something that you think might make your experience with [CONDITION] better today. You can choose any time point from yesterday, all the way back to when you were a child. Think for a moment . . . now, please describe to me what time point in your life you’d go back to and what you would tell your earlier self to make your experience better today?” This taps into reflection and resilience.

- Fill-in-the-Blank: “If I heard that my friend was going to develop [CONDITION], I would feel [BLANK] because [BLANK].” Or, “I wish my doctor could understand [BLANK] about how I am feeling.” This reveals unmet needs and emotional complexities like regret, guilt, or hope.

- Best, Typical, Worst Days: Asking participants to describe living with their condition across these scenarios uncovers emotional swings and coping mechanisms. It also recognizes emotional complexity and validates that people experience a range of feelings about their condition.

These methods are examples of ways to relax participants, foster creativity, and accommodate time constraints by presenting prompts separately and adapting based on responses.

Engaging with Compassion

Compassion is the cornerstone of this work. Seriously ill patients may carry unexpressed fears or sadness, often hidden behind a “mask” worn to protect loved ones or healthcare providers from their true feelings. Researchers may be the first to hear these unfiltered emotions, a responsibility that demands active listening without judgment. Our role is to free the person behind this mask, creating a safe space where their authentic voice can emerge. Don’t be surprised when they let their guard down and you see a lot of pent-up fear or sadness. Interviewers need to respect unveiling by listening attentively with great sensitivity while still staying on task for our clients. Balancing these components is truly an art.

Words Matter

Terms like “heart failure” or “end-stage” can feel like a death sentence, even if manageable . . . so avoid clinical jargon unless participants initiate it. People handle this differently. Some are knowledge- and terminology-hungry and want to be clinically correct. They research and may learn almost as much about the condition as a healthcare provider. When talking with these people, they may sound very clinical, as if you were speaking to a healthcare professional.

Others may have a hands-off approach, wanting to think about their medical issues as little as possible. It is important to understand that they may recoil at certain words. When possible, be attuned to this and mirror their own language. If a person routinely says, “my condition,” or “my heart trouble,” it is OK to use similar language during the conversational parts of the study. Obviously, there are times when your language must be precise. But try to mirror the person’s language as much as possible to avoid repeatedly hitting a soft spot.

Flexibility is Key

Take breaks if needed, schedule buffer time to process tough conversations, and allow tangents rather than redirecting abruptly. Ask your clients to be mindful that minimizing excessive probing or off-topic questions helps to preserve focus and trust.

Understanding Emotional Complexity

Participants exhibit a broad spectrum of emotions—fear, isolation, resilience, hope, confidence, doubt—which are often revealed through projectives. Some focus on positives like effective treatments, while others describe barely holding on. Coping mechanisms, support systems, and feelings of judgment from family or providers also emerge, offering clients actionable insights.

Past unhealthy choices may result in feeling blamed by others for developing the

disease. Patients may also feel they are disappointing their loved ones if they struggle with daily activities or request healthier meals, which may take away from the enjoyment of family gatherings. Financial strain on the family budget related to the cost of care and/or loss of income can be overwhelming.

Retaining Moderator Focus

Moderating sessions with individuals living with chronic or life-threatening illnesses can be emotionally taxing for the moderator—demanding resilience and self-care. It is important to acknowledge this and allow time to decompress. Some strategies include:

- Set realistic limits—fewer daily sessions.

- Take meaningful breaks (e.g., outdoors or in quiet reflection) to reset.

- Set a minimum 30-minute buffer between interviews to allow decompression and preparation.

- Prepare for the (rare) circumstance where a participant becomes truly distressed by keeping resources like counseling or suicide hotlines accessible and dismissing live listeners if a participant becomes overwhelmed.

Advocating for Patients

Adhering to industry guidelines (e.g., CASRO, QRCA, ESMO), moderators act as stewards of participants’ well-being, ensuring they leave feeling valued and respected. My company maintains that patients with serious illness have the right to:

- Receive Honest Communication: Patients should not be given false hope when shown new hypothetical medical developments. Moderators must clearly communicate that what they are viewing may never be available or may not be appropriate for them.

- Be Heard with Compassion: Patients deserve attention and empathy without judgment.

- Understand the Moderator’s Role: The moderator is there to facilitate this person’s communication with the research sponsor and ensure they are well-treated during the process. The moderator is not a medical professional and will not give medical advice.

- Know How Their Input Will be Used: Patients should understand, at least generally, how their feedback will be utilized. Explaining how their opinions may help future patients is meaningful to them.

- Take Breaks as Needed: Moderators should be aware of signs of fatigue, confusion, or agitation, and offer breaks or adjust the conversation accordingly.

- Leave the Interview Feeling OK: Every effort should be made to ensure that patients end the interview in a better or similar state of mind as when they began.

Conclusion: A Call to Action

Research with seriously ill patients is a privilege and a challenge, requiring meticulous preparation, compassionate execution, and steadfast advocacy. By blending rigorous methodology with human sensitivity, marketing researchers can uncover insights that drive meaningful change in healthcare—informing pharmaceutical strategies while honoring the humanity behind every data point.

Have you faced strong emotions in a session or supported a loved one through illness? These experiences underscore why this work matters and why moderators must get it right. Collectively, qualitative researchers can refine how we listen to those who need to be heard most.