By Sebastian Murdoch-Gibson, Founder and CEO, QualRecruit, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, sebastian@qualrecruit.com and Jonathan Armstrong, Partner, Cordery Compliance, London, United Kingdom, jonathan.armstrong@corderycompliance.com

It’s 2015. Fetty Wap (remember him?) and Wiz Khalifa are taking spots on the Billboard Hot 100. Though they might own the summer, the fall belongs to the enterprising Austrian privacy activist Max Schrems. On October 6, his complaint to the Irish Data Protection Commission, challenging Facebook’s transfer of his personal data to the United States, throws the world into data turmoil. Facebook, like many tech companies, bases a lot of their operations out of Ireland for tax purposes.

The European Court of Justice (ECJ) finds the U.S.-EU Safe Harbor Program, which over 2,000 companies had relied upon as their legal basis for moving personal data from the EU to the United States, inadequate to protect the rights of EU citizens under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The effects ripple out through the economy. Global HR platform providers based in the U.S. become unsure of their legal ability to run payroll to EU nationals the following week.

In the seven years since, nobody has seemed to figure out how to move data between the world’s largest economy and the world’s largest economic bloc to everyone’s satisfaction. One successor to the Safe Harbor Program has already been invalidated by EU courts, and the alternative methods of legally sending EU personal data to the U.S. are complex and difficult to comply with.

The implications for our profession are clear: as data professionals, few can say they have more exposure to privacy regulations than qualitative researchers. By the nature of our profession, we are regularly entrusted by our respondents with the most sensitive (and protected) categories of personal information. With more fines being issued under GDPR in September 2022 than in all of 2021, relying on a broken data transfer framework to protect the movement of EU data to the U.S. seems increasingly like an untenable risk.

Last October, seven years to the day after the ECJ decision striking down the Safe Harbor agreement, President Biden signed executive orders intended to bring the United States into compliance with the terms of a new “Trans-Atlantic Data Privacy Framework” that would permit data concerning EU nationals to be transferred to the U.S. without violating GDPR. So, it would seem, the U.S. and EU are on the verge of figuring this out.

Should we be relieved?

I spoke to Jonathan Armstrong, partner at Cordery Compliance, host of the award-winning Life with GDPR podcast, and, in my humble opinion, the most entertaining compliance lawyer out there, to learn more about this topic and his perspective on what market researchers can do to navigate the privacy landscape in the meantime.

Sebastian: How would you describe the data transfer regime that GDPR established?

Jonathan: Whenever you’re looking at data transfer rules, you have to start with data protection. As a general rule, the countries that make up the EU have had data protection laws in place for some years prior to GDPR. That’s taken two formats: first, there was in-country legislation, and then there was an EU directive that was sort of replaced by GDPR. Looking at that background is really important because a lot of the predirective legislation is a testament to concerns that people in Europe have had about the holding of their data, usually because it relates to World War II or the former Soviet Union.

Countries that have had experience with the Nazis (for example, recognizing Jewish citizens by their dental records), have this real hard-felt foundation of data protection/privacy law because they can see the harm data can do. Some years ago, when Romania and Bulgaria were joining the EU, the European Commission ran an event in Bulgaria where I spoke. One of the delegates, from Latvia I think, said to me, “You will never understand how important data protection law is until your neighbor is taken away and shot in the middle of the night.” You know, most of us do not have this innate cultural understanding of how important data protection is.

A lot of that sensitivity comes from what oppressive regimes have done with people’s intimate personal data, but “personal data” is a much broader definition than personally identifiable information (PII) in your part of the world. So, we’re not just looking at things like bank details; we’re looking at things relating to “me”—and that might be my health, my marital status, whether I’m in a trade union or not, or it also might relate to things that I possess if they can be tied back to me.

It could be the device identifiers on my cell phone, or my IP address, or my geographical location. Geolocation, for example, can be truly problematic for any organization to deal with because if you set up geolocation, you often accidentally get sensitive personal data as well. For instance, you might be able to pinpoint me to a place of worship, which would disclose my faith, or you might pin me to a particular ward in a hospital, which might indicate health concerns that I have.

So, as a general rule, whenever you’re doing any processing of data—and “processing” is really broadly defined—then you’re going to come up against data protection law.

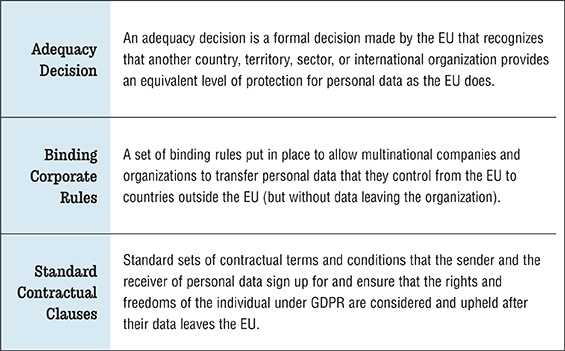

The cousin of data protection is data transfer law. Effectively, what it says is, “If you are going to transfer personal data outside of the European Economic Area (EEA) or U.K., then you need to have some additional measures in place to make the data transfer lawful.” That could be an adequacy decision, which Canada has, but the U.S. hasn’t. It could be using binding corporate rules. It could be consent, although consent is really tricky even in a market research environment. Or it could be under standard contractual clauses (SCCs), and that’s probably the most common method.

There used to be a method of transferring data from the EU to the U.S. called Safe Harbor. That mechanism was knocked down by a court case. It was sort of stood back up again as a scheme called Privacy Shield, but again, that was knocked down by a second court case.

There have been ongoing efforts to try and resurrect Safe Harbor, with both the U.S. authorities and EU authorities talking about this resurrection, and every now and then they’re saying the “negotiations are going very well; we’re very close.”

Sebastian: Tell me a bit about the Safe Harbor program and how it enabled the transfer of data between the EU and U.S.

Jonathan: Safe Harbor started as a scheme of legitimizing the flow of data from the EU to the U.S. Effectively, it works a bit like a “trump card” in a game of cards where you can say, “if you are transferring from the EU to a U.S. organization that signed up for Safe Harbor, and abide by the rules of Safe Harbor, then that transfer is safe.” The fiction is that the receiving organization will guarantee the same respect for data that data protection law in the EU demands.

Safe Harbor was knocked down by a man named Schrems (mentioned earlier in the article), who was then an Austrian law student. An important part of his background is that he is Austrian, and people in Austria are fearful of the way in which the state uses their personal data. Not necessarily because they are fearful of the Austrian government, but because they are fearful of the time under Nazi occupation when bad things were done with data.

He made a subject access request to Facebook. (Data protection law enables you to make these things called subject access requests, where I can say to you, “I need you to tell me all the data you’ve got on me.”) He received approximately 200 pages of data that Facebook had on him and he thought, “Hmm… that isn’t really enough. There must be more data that Facebook has on me.”

So, it started off as a complaint to the Irish Data Protection Commission saying effectively, “I believe there’s more data, and Facebook hasn’t been transparent as to the amount of data it has on me.” At the same time, there were also concerns about the transfer of that data, in particular, if Facebook could guarantee that the U.S. government would not be looking at Schrems’ data that was transferred to the U.S. This is around the time of the Edward Snowden allegations that the National Security Agency (NSA) was spying on people, so how could Facebook assure Schrems that the NSA would never see his data?

When the ECJ ruled, they went further than the question they were asked, and they said the entire Safe Harbor scheme was invalid (insofar as it couldn’t protect against this kind of intrusion). That set a panic in motion. When I talked about these things to Mr. Schrems, he said that really wasn’t his intention; he was somewhat more focused on Facebook and didn’t expect the whole of Safe Harbor to collapse.

While there were only, from memory, about 2,000 corporations in Safe Harbor, it had a much wider effect because a lot of organizations used global payroll providers and global HR solutions that relied on Safe Harbor to legitimize their data transfers. For a time, businesses were saying they couldn’t pay their staff because of the collapse of Safe Harbor. In the years that followed, there was a move to replace Safe Harbor with another scheme called Privacy Shield. The European commissioner at the time managed to persuade the Obama administration to make some concessions, which she said effectively cured all the issues the ECJ had highlighted in their ruling.

Now, not many people who followed this thought that was true. I certainly thought that Privacy Shield was a dead man walking, waiting to be attacked again by the courts. I interviewed Schrems in 2016 on the topic. I think he described it as “Safe Harbor with flowers on it.”

Eventually, the Privacy Shield scheme went to court. The deal was done with the Obama administration, and being as politically neutral as I can, it was not super helpful that Obama had been replaced by Trump in the interim. There were some… Post-It notes, if you like, that the Obama administration had left for the Trump administration that never got picked up. For example: “You need to appoint a privacy commissioner. This is done by executive order.” But, for whatever reason, those Post-It notes hadn’t been picked up, or, if they were, they were picked up too late. That meant that Privacy Shield was also under scrutiny and eventually knocked down by the court. The court this time also went further and said that they didn’t think that SCCs as an out-of-the-box solution worked either.

Sebastian: For the benefit of the readers, can you tell us more about what a SCC is?

Jonathan: It’s effectively like a form agreement. It’s a longish agreement that you can’t really alter. It contains typos, and it isn’t in super helpful language.

But it effectively commits the party receiving data outside of the European Economic Area (EEA), or the EU, or the U.K., to observe the same principles as if they were bound by GDPR. They also have to commit to things like security measures they’re going to apply to the data, etc.

Sebastian: The court basically determined that this alone is not sufficient protection, right? If the NSA comes knocking and Facebook has data they want, Facebook can hardly say, well, we have a contractual commitment that supersedes your right as a sovereign national authority to take this data. Is that more or less what the court found?

Jonathan: Yes, that’s right. So, there’s a need for this double-due-diligence. First, you need the agreement in place. You need to make sure the entity you’ve signed with is reliable. But now you also need to either determine that there are no governmental overrides in the jurisdiction you’re sending the data to, or, if there are governmental overrides, you need to set out how you’re going to overcome those. That might be through encryption, it might be to reduce the potential harm by giving a right to make representations to government authorities, or whatever that might be. However, some argue that there is actually no way of making a transfer to the U.S. under adequate protections because the U.S. authorities basically have the right to get whatever they want, including the right to break any encryption.

Sebastian: In October, the Biden administration announced executive orders intended to bring the U.S. into compliance with a new data privacy framework (DPF). When you and I initially spoke, you compared the administration’s teasing about the DPF to “a high school holiday show where nobody else is allowed in the room during rehearsals. Every now and then somebody pokes their head around the door and says, ‘You’re going to love it. It’s going to be great. It’ll be the best thing you’ve ever seen!’, but invariably the result is pretty lame.” How does that prediction hold up?

Jonathan: What would the word be…? Sadly, right. I suppose I was hoping it would be something better, but I’m not sure it is. Has the Biden administration listened more? I think yes. They clearly looked at the court judgment and thought about what they could do, rather than just rubbish the judges, which some in earlier U.S. administrations have done. But have they made meaningful progress that will make for a secure deal? No. I suppose, in fairness to the Biden administration, constitutionally, that’s a tricky thing for them to do.

The main idea is to try and address the worries that the court had on the Privacy Shield scheme. The main one being giving individuals a right to complain [to a U.S. privacy tribunal]. There’s some other things in the executive order as well. For example, dropping GDPR-like wording into instructions for the security services that they’ll only process data in a proportionate way. But I think the crux of it is to try and give EU nationals or those under the GDPR regime a right to redress in the U.S.

What’s perhaps different since we last spoke is that most people thought the challenges would come after the event. DPF would come in, people would complain about it, and proceedings would then be issued. But what Schrems and his pressure group NOYB are saying is that, if the scheme has the faults in it that they think it will have, they might be prepared to issue injunctive proceedings that would stop the scheme from actually being introduced.

What could change the situation would be U.S. federal privacy legislation. But I don’t see that happening in time for a quick deal. I don’t think that the promise of privacy legislation on a federal basis will be enough.

There is some talk about different U.S. states trying to splinter off and do it alone. What I mean by this is that some U.S. states might claim that they are adequate even if the whole of the U.S. is not. We’ve definitely heard talk that California, for example, might use the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) to apply for its own adequacy decision, and might enter negotiations with the EU. I’ve seen all sorts of constitutional debate as to whether that’s even possible. My suspicion, regrettably, is that the third show is going to be as disappointing as the first. So I’m not buying a ticket for DPF as something that will last. There’s clearly an impetus to do a deal between the Biden administration and the European Commission; I’m just not sure that either of them can deliver what they think they can.

Sebastian: The basic incompatibility seems to be the legislative authority that the U.S. government has to access personal information for national security reasons, right?

Jonathan: Yes, that is the case. But, for example, the EU does have adequacy decisions with Canada, whose security services have access to personal data as well. The EU has an adequacy decision with Japan, and when I was in Japan a couple of years ago, I think that was a source almost of merriment to some people. But, in Japan, as I understand it, their security services have wider powers with less supervision than the U.S. Yet, the European Commission trumpets the fact that it has an adequacy deal with Japan, but rejects the possibility of doing one with the U.S. I think part of it is the legacy of Snowden. The U.S. not only has a problem with having overreaching legislation, but a problem with people perceiving that they use that legislation on a regular basis.

Sebastian: Where does all of this leave us right now in terms of how we can legally execute transfers of personal data between the EU and the U.S.?

Jonathan: Look at the principles of GDPR. So, look at not only how you’re going to transfer data, but whether you should collect it at all, and whether you should be transferring it at all. To give you an example, if you’re trying to do a survey on whether I like cheese or not, then you don’t need a lot of data on me for that survey. Do you need to know whether I’m Catholic or Protestant? Do you need to know my sexual persuasion? You might need to know my age. You might possibly need to know my ethnic origin, because, you know, if I’m Polish, am I going to favor Polish cheese? If I’m French, am I addicted to Brie? If I’m Swiss, am I addicted to Emmental? There might possibly be justifications for things like that. But you’ve got to always have the minimum dataset you need to accomplish your goals.

Then you have to ask yourself, “How long do I need this data?” “What’s the purpose?” Be transparent with people and say, “This is the data I’m going to obtain, and this is how I’m going to use it.” Put where you’re going to process the data in that transparency communication. So, you’d say, “By the way, we’re going to transfer your data to the U.S., and we’re going to legitimize the transfer by SCCs.” You might call all this the “prep” piece, where you make sure that the data are collected and processed lawfully before the transfer takes place.

The transfer piece usually is going to be done through SCCs. You’re going to work out who you’re going to transfer the data to, and you’re going to do a bit of due diligence on that organization and have them sign SCCs. You’ll also do a bit of due diligence in parallel on the jurisdiction where they’re based and how the laws there protect privacy. This part might be called a “transfer impact assessment” or a “data transfer impact assessment.” By the end of it, you’ll have filled in a questionnaire that you’re going to staple to your compliance file, and when a regulator knocks on the door, you’re going to be able to show it to them. Then you can say, “this is the exercise we did to work out the data we needed and why. Here’s another document that shows that we’ve gone through double-due-diligence prior to signing the SCCs to legitimize the data transfer.” If you can do these things, then broadly, you’re going to be OK.

Be the first to comment