By Wendy Pease, Owner and President, Rapport International, Boston, Massachusetts, wendypease@rapportintl.com

“The key to successful multilingual research is uniformity. A solid framework means processes are as standardized as possible.”

Growing up internationally—in Mexico, Taiwan, the Philippines, and the U.S.—made it easy for me to fall in love with different languages, cultures, and diversity of thought and expression. I’ve embraced and promoted this ideology in everything I’ve done since, especially when cultivating my company focused on high-quality translation and interpretation. Our mission is to connect people across languages for a kinder and more prosperous world.

Language translation and interpretation are among the well-known stumbling blocks on the way to meaningful and reliable qualitative research outcomes. Yet the benefits of a diverse group of participants are clear across every industry. Just as companies that employ a diverse workforce—of differing cultures, ethnicities, genders, ages, scholarship, expertise—see greater innovation due to varied, nontraditional, even disruptive viewpoints, research stemming from diverse viewpoints promotes equity in all outcomes while improving products and services. Throughout, such diversity is also better representative of the oft-changing international business landscape.

Understanding how language can influence research outcomes and knowing the translation and interpretation options for conducting multilingual research contribute to effective project planning and a reusable framework. Here we describe our work with a healthcare research company looking to improve the lives of adults living with diabetic kidney disease (DKD). The project highlights the language and cultural adaptation issues that commonly transpire at each stage of any research project and how planning helps to mitigate these issues.

The Devilish Details

There are over 7,000 living languages, each adding thousands of new words to its lexicon annually. According to Ethnologue, however, roughly 40 percent of languages are now endangered (with fewer than 1,000 speakers remaining), and just 23 languages account for more than half of the world’s population.

So, piece of cake, right? On the contrary, just consider the title idiom, vive la differénce! It’s borrowed from the French, literally translated as “long live the difference:” vive (“long live”) + la (“the”) + différence (“difference, diversity”). This is correct and unremarkably French until you google vive to find that Parisians say it differently. The idiom is decidedly not French in its usage, common only in the U.S. and other English-speaking countries.

With 7,000 new words per lexicon each year, differences in international cultural norms, and the multifaceted researcher-respondent-translator/interpreter relationship, it’s no wonder that translation gets in the way of qualitative research, itself a subjective undertaking.

Work Smarter—A Case Study

Our client’s DKD research project reflected this complexity. The goal was to find an actionable way to transform the treatment—and the day-to-day quality of life—of adults living with DKD. To do so, they used a collective case-study approach, which aligns and differentiates between individual cases to extract meaningful qualitative data, garnered from physicians and patients from the U.S., U.K., Germany, and Japan.

The project required the implementation of a translation management strategy, which details the language requirements for each research stage: the number of translators and interpreters needed, key documents and content to be translated, and the process for quality assurance. In this context, the language services provider works as a cultural arbiter, in addition to a translator, for everything from recruitment strategies to interview methods and printed collateral.

The core research stages take slightly different names but generally track across industries and take the qualitative shape of (1) planning, (2) recruitment, (3) interviewing, and (4) analysis and reporting.

First and foremost, the key to successful multilingual research is uniformity. Not to be confused with simplicity, a solid framework means processes are as standardized as possible and designed to inspire trust, starting with:

- Consistent terminology. Codify important terms and standardize glossaries (see Visual A: Translation Glossaries) in every language and across all document types, for everything from notes and memos to recorded data and data analysis. The French, for example, will often coin new terminologies instead of adopting English words; in fact, they created the General Commission on Terminology and Neologisms for just that purpose, to stymie the use of English words. But it gets pas d’amour (“no love”) from the IT industry, as no French person actually confirms receipt of “courriel” or automatically deletes “le pourriel,” instead just receives “email” and ignores “spam.” (The Québécois, on the other hand, embrace la différence!) Ultimately, it’s essential to know the language is rife with neologisms that will need to be specifically defined for clarity.

- Cultural adaptation. Countries can often be classified as high- or low-context cultures, which helps when choosing a communication method. America and Germany are examples of low-context cultures, relying on explicit verbal communication; bulletin boards or interpreted phone interviews could work just fine in certain contexts. Japan, France, and Brazil are high-context cultures. They communicate in ways that rely heavily on customs and narrative or implied context, as well as body language and other implicit cues; video interviews with an interpreter or face-to-face interviews are more effective.

Project Methodology

With an overall goal toward “uncovering deep emotional and behavioral insights that shed light on the physician (and patient) DKD treatment and management experience, and the underlying unmet needs, aspirations, and expectations,” recruitment of the right participants was essential. Prior to any physician or patient interviews, our client conducted preliminary web-based video interviews with a small number of physicians to refine the screener.

The resulting screener qualified physicians from multiple disciplines who then completed an “Online Spotlight,” a qualitative pretask (text-based) designed for reflection.

Subsequently, experienced moderators conducted in-depth telephone and in-person interviews with these physicians to complete the process.

Physicians referred patient participants who were asked to maintain an online diary prepopulated with daily questions and encouraged to also submit written reflections and illustrations.

- Planning. Besides constructing a team of dedicated translators, determining project languages and the essential content to translate during each research phase, we also worked with researchers and moderators to identify specific language issues that may arise during the subsequent phases.

Translation issues involve insufficient planning, uncoordinated efforts between departments, and inconsistent use of translators. We encourage clients to take their time here, and to document and standardize processes as much as possible. Uniform glossaries of terminology are crucial for consistent meaning across the studies and provide the researcher with a formal system by which to organize and identify meaningful associations within the data.

Planning also means working with researchers and moderators to determine the best-suited combinations of translator/interpreter and research method, based on the scope and nature of the research. We’ve seen IT qualitative research thrive with nonnative multilingual moderators, while healthcare requires moderators with native-speaker fluency to draw out multidimensional responses. Both speak the respondent’s language, yet to elicit personal information, it often helps to also share a culture or country of origin.Elements to consider at this stage might include:- Will you use in-country recruiters and moderators in each participating country versus multilingual nonnative researchers via phone/online interviews?

- Will an interpreter with native fluency be sufficient, or do you require someone with industry experience also?

The scope also determines the formality of documents that require translation—clinical trials will require more regulatory vigilance than our client’s project, which prioritized narrative and emotional data.

- Recruitment. By the recruitment phase, project languages are identified.We translate recruitment documents and discussion guides and provide guidance on the cultural propriety of images and pictures in online recruitment content—translated social media, informational documents, and landing pages—making sure they reflect the makeup and culture of your preferred respondents. Even colors can make a difference!We also help with tailoring recruitment interviews based on project goals and cultural fit. Knowing the difference between high- and low-context cultures helps when crafting these documents.For example, the articulation question asked physicians for an analogy or metaphor to represent how they felt about their current work environment. The request elicited creative, “outside-the-box” responses from French and Japanese physicians, but was met with bland, lackluster responses from American and German physicians. High-context cultures are more group-oriented, so the question resonated; they feel more invested when part of a group effort. To coax a similar level of response from the low-context countries, which place greater emphasis on individualism, we simply altered the question to inquire into the physician’s role within their workplace, to meaningful results.

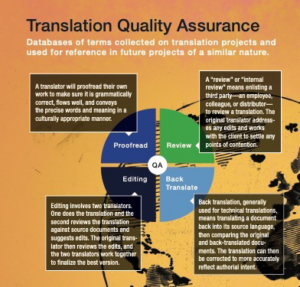

- Interviewing/Data Collection. The interviewing phase is fascinating because individual qualities and personalities continue to emerge—a multilingual person might use specific hand gestures only when speaking certain languages.Our client, for example, quickly realized that the treatment of DKD was exceptionally affecting for attending physicians. The disease is often asymptomatic and, once identified, impossible to reverse and difficult to curtail; many respondents described feeling simply “powerless.”Using interviewers (and translators) with native fluency in the respondent’s language was key to capturing the intensity and precise meaning behind these physician accounts, as opposed to using multilingual but nonnative speakers. For that same reason, quality language service providers will keep the same translators with the same clients over various projects, to guarantee both consistency and value.Yet, certain cultural differences initially unaccounted for might emerge during fieldwork, and we adapt. In this phase, our client determined that Japanese physicians were less responsive during the final phone interview than was indicated by their initial online spotlights and when compared with French and German accounts. An informal participant survey showed that, due to the emotional intensity attached to the subject, Japanese clinicians preferred in-person interviews; thus, an option was added to the process.On the patient side, we translated the daily journals of 64 adults with type 1 diabetes. Just as moderators derive a lot of value from the use of projective techniques, translators relied on patient drawings and patient-authored captions to various images to get a sense of the patient’s mood when responding to intimate diary questions and guide translation of said responses.Respondent accounts are very personal and subjective, and we found that translators’ interpretations leaned sometimes more emotional and sometimes more rational. Such differences are only natural and exactly what gives depth and nuance to every story while also introducing a second layer of subjectivity to the data. To ensure quality and clarity, we implemented the “TEP” process of translation, editing, and proofing for patient diaries (see Visual B: Translation Quality Assurance Graphic). Here’s how it works: one individual translates the account, then hands it off to a second translator to review and refine. The translator and reviewer then work together to come up with the “best possible” version of the piece and then one of them, or even a third party, does the proofing for style and substance.

- Analysis and Reporting. Uniformity throughout helps to organize the data during analysis and reporting. If a certain terminology appears consistently across respondent accounts, patterns will easily be revealed during the analysis. Even elusive concepts like “fragility” or “powerlessness” can be identified if used often enough among translators and codified consistently across languages. At times, AI or machine translation may seem helpful for finding these patterns, yet even as it evolves, the nuances of language inherent within qualitative research—dialects, local language, cultural references, and slang—remain compromised.

Et Voilà

Skilled translators and interpreters possess native language fluency in project languages, as well as specific industry experience. They are well-versed in the modes of communication culturally appropriate to a participant’s country of origin. A high-quality language service provider will “matchmake,” in a sense, when assigning personnel to a project. Doing so builds a level of trust that, as with any involved relationship, guarantees understanding and clear communication, even if you don’t always speak the same language.