Editor’s Note: The author provides a snapshot of how the Chinese research community was able to adapt to restraints imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Prologue

At the end of 2019, I had declared that my intention for 2020 was LOVE and even wrote it on a vision board.

Ironically, a series of disasters came not long after this intention was written. My cat Vickey died on the surgery table. One of my friends died of food poisoning. There was this moment in February when I found myself stranded in Texas, after the 2020 QRCA Annual Conference, struggling to find a flight ticket back home. COVID-19 had shown up out of nowhere, and flights from the U.S. to China were severely curtailed.

Today, as wearing a mask has become an inescapable habit, I ponder and reflect on whether my year’s intention still applies.

Fast Forward to Present Day

I started thinking about this article in October 2020 while staying in a four-star hotel located on the east side of Shanghai on one of the national holidays. Domestic tourists were rushing to Shanghai, tripling the typical number of visitors. The hotel breakfast floor was full of people. There was not a single sign of COVID-19’s impact, except for masks hanging loosely around people’s chins. While public locations like the subway or movie theaters still have strict mask and social distancing policies, in other places (like neighborhood parks, offices, and coffee shops), most people go mask-free when talking to each other. There is a warning of the virus kicking back in over the coming winter, but it does not seem to push people to act more cautiously, as most of China has been keeping cases at zero for months. As a contrast, in January and February 2020, the streets of Shanghai were empty and everything was locked down, like many other places in China.

Still, looking beneath the happy faces in the street, China saw a disturbed market and economy undergoing reconstruction. Even though most Chinese people went back to work in early March, the ongoing virus changed people’s mindsets and impacted the political and economic environment. Many shops along the streets were closed and considered reopening under a new label. Industries within the food supply chain, travel and hospitality, airlines, and entertainment barely caught their breath while dealing with a cash flow shortage. International trading companies suffered from a high level of anxiety, having their eyes on the international news and the exchange rate fluctuation. On the bright side, though, the virtual economy flourished, starting from e-commerce players, video gaming companies, online education enablers, online technology providers, social media like TikTok, and online-streaming platforms.

Market research and consulting businesses were under a lot of pressure in the first half of the year. In-person research was completely cancelled from mid-January to March and conducted cautiously from March to May. Cash flow for businesses in these industries was difficult during this period, forcing some to cut off employees’ paychecks. In June, though, the project numbers started rising again. By the end of 2020, everybody—including freelance moderators and small-to-big-sized agencies—was quite busy.

The silver lining is, in fact, the spirit and the innovation coming from individuals and agencies as a result of COVID-related challenges. Here is what inspired me.

The BOOM of online research

During the darkest months of January to May, active projects shifted to online methodologies. International research projects used global online platforms including Recollective, Together, Zoom, and Microsoft Teams, all of which support multiple languages and are familiar to global clients. Closer to home, local projects started to test domestic platforms that typically only support Chinese languages. Large agencies like Ipsos had proprietary online community and online chat platforms ready. Smaller agencies increasingly used the free chatting apps of WeChat, QQ, and DingTalk.

One week after lockdown, it seemed everybody had become an online research expert. After May, however, offline projects started to bounce because in-person conversations and observations were still held as the best way to uncover deeper insights. Online qual did not go away, though, as it had proved itself cheaper, faster, and able to reach nationwide, diverse consumers.

Thirty percent of my projects in the past three years had already included an online approach; mainly an online community or one-on-one video in-depth interviews. In 2020, we increased the rate at which we supplemented online face-to-face research with mobile ethnography. Moving forward, we will definitely stick to mobile ethnography and mini online FGD (focus group discussion) methodologies—especially for private, intimate topics (related to female health or sexuality, for example), where consumers feel more relaxed wearing pajamas at home. However, in China, we will not recommend video focus groups with more than four people per group because it is difficult for them to interact with each other and typically takes one-and-a-half times longer than offline FGD with the same discussion guide.

Visionary players capitalized on this opportunity to grow

China’s market research and consulting industry already had its challenges before this crisis. With the quick change of the retail and media environment, clients were leaning toward more agile and result-oriented research solutions. Second, because of their different media habits and social codes, the younger generation posed the need to find new ways to recruit. Agencies that had been adapting before the crisis saw the fruits of their flexibility during this tough period. Such agencies include:

- Those who offered integrated services such as market understanding, strategy, creativity, media, advertising, and events implementation. Such full-service businesses were able to overcome the communication hurdles between these “silos” when being handled by different agencies.

- Those who focused on new technology-enabled research; for example, online research platforms and AI analysis tools.

- Those who had implemented novel recruitment strategies, including partnering with e-commerce platforms, social media celebrities, or starting one’s own community with one’s own social media or event series. Alibaba Group, for example, uses e-commerce platforms like Tmall and Taobao to identify the specific respondent profiles and send research invitations for in-house and outsourced research projects.

- Those who observed trends using social listening tools, culture decoding methodologies (i.e., semiotics), industry experts’ interviews, and cross-industry studies for deeper insights.

- Those who switched to big-data analysis services.

What about Small Qualitative Research Businesses?

Being a tiny player in the research industry of China, my team of three has been doing some soul-searching and change management, just like everyone else. Here is what we have been doing and experimenting with since January 2020:

- Upgrading our online facilities for a better experience with respondents and clients. They now include professional lighting (one big stand-up LED circle light and one small table LED light) and microphones (we use Audio-Technica 2500). We researched and mainly got inspiration from seeing the gear of online hosts in the live-streaming business, which has been hot in the past five years in online entertainment and online commerce.

- Prioritizing the team’s safety. If a project requires physical presence in a risky area, we will say no.

- Going back to offline interviews. After May, we implemented safety measures, like wearing face coverings, providing plenty of disinfecting products, hand sterilizer, and wipes in the facility, and inviting fewer people (four to six) to keep a proper social distance. The main difficulty we faced was that wearing masks and keeping distance required that both the moderator and the participants speak much louder than they normally would, which proved to be tiring. We tried transparent facial masks with perforations on the side but dropped them because we were not fully comfortable with the protection capacity. All this increases recruitment difficulty. On reflection, I would rather keep all interviews and focus groups online (except sensory tests that require strictly controlled processes/protocols) until masks are not a requirement anymore and everyone feels safe enough to remove their coverings. For regular sensory tests—like testing the scent and touching/using a product—we successfully experimented with sending the products to participants’ homes for online video focus groups. The participants opened the package live in the video FGDs, tried, commented, and discussed as a group.

- Expanding our skill set as qualitative researchers. COVID-19 gave us more time to discover and train for new skills. One of these is leveraging the power of visual communication in research. Clients’ need for insights unbiased by language precedes the COVID-19 era. Visual facilitation, also called graphic facilitation, is using imagery plus text to record or express information in the meeting setting, which facilitates group discussion or brainstorming. All team members were trained in sketching and, for example, can draw the innovation ideas out of the interview as part of the report delivery. Some younger team members have had this kind of training in school, but the rest of us took drawing classes and visual facilitation training to acquire a new set of skills that we now use in both internal and external meetings.

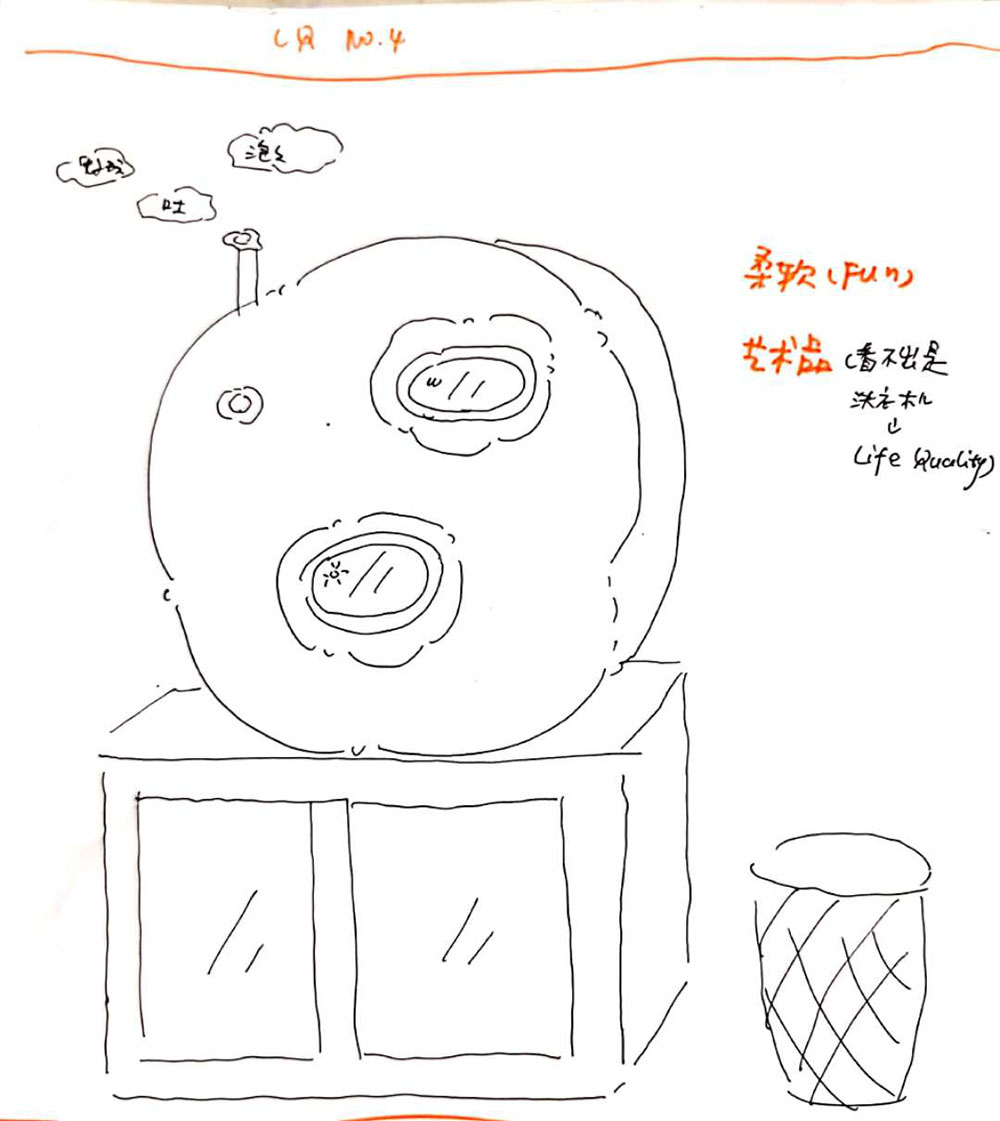

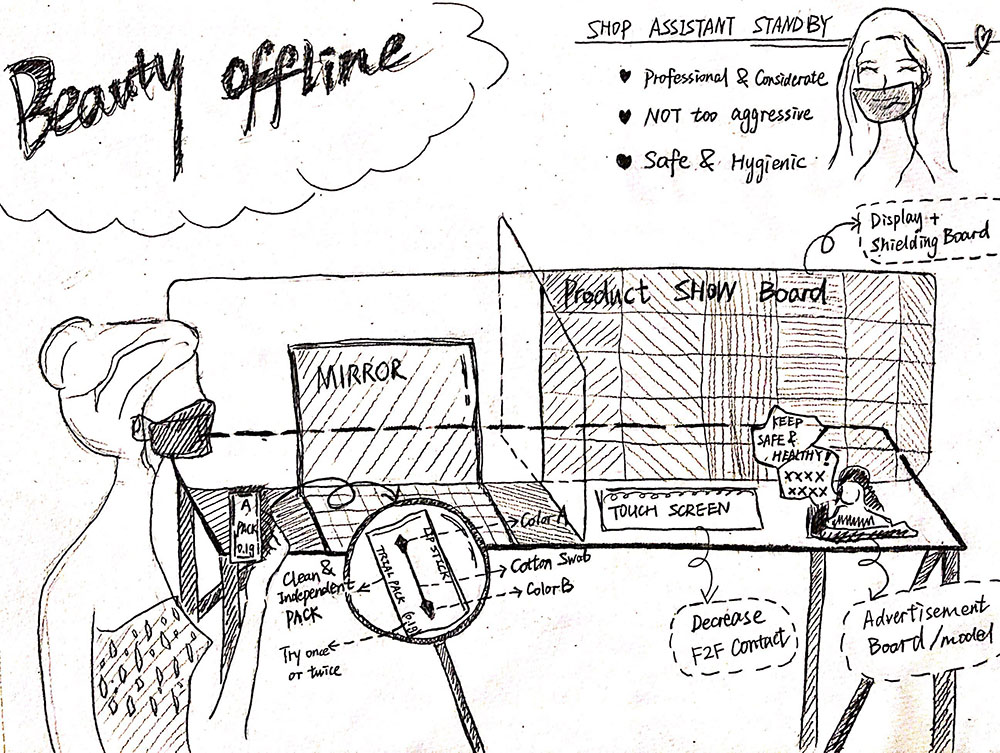

Sketching can draw innovative ideas out of interviews. This drawing of an ideal washing machine was created by Rachel Wang. Another skill set that just made it to our toolbox is video making and editing. International clients are now unable to travel to China to meet their consumers. Normally, they would have requested a city visit plus the consumer visit and some accompanied shopping sessions. These clients are also eager to see and feel the Chinese consumer’s life today, and they cannot get it from the media, which is too generic, not specific to their needs. We have expanded our skills into creating various types of video-based insights, from mini-documentaries to hot-topic featured videos.

Expectations of offline retail innovation, illustrated by Aileen Zhang.

- Building cross-cultural bridges by sharing cultural insights in domestic and international social media.

- Implementing a personal style transformation. This started with me being accused of not being stylish enough for fashion projects. It encouraged me to take fashion training together with stylists and professional buyers. Classes included Asian color systems and clinics, individual style clinics, clothing collocation, closet management, buyer training, and hairstyling and makeup. I ended up changing much of my personal style, and so did my team member Aileen. Yes, I have become more qualified for the fashion projects as I wished, but it was also an experiment that sparked many debates about visual codes of masculinity and femininity in the Chinese culture—an experiment that wouldn’t have been possible (maybe) if these COVID-19 times hadn’t pressured us to think about what our life could be and what different choices we could make.

Rachel was prompted to implement a personal style transformation, as depicted in this photoshoot by Richard Lu, copyright owned by Rachel Wang.

Conclusion

The pressure to innovate due to COVID-19 enabled me to integrate so many things I love into the way I conduct business. In fact, my intention to always start from a place of love still found its way into 2020, and from the very beginning of the year! Right after I got stranded in Texas, a dozen angels from QRCA extended their love to me by offering a place to live, saying comforting words, connecting me to useful resources, praying with me, and driving me to the airport. Their acts of love warm up my heart and help me to stay strong. I hope my own behavior followed their example and extended some love to the world. Thank you, Isabel Aneyba, Janet Standen, Marc Engel, Caryn Goldsmith, Judith Wright, Dina Shulman, Marissa Brown, and many more!

Be the first to comment