By Sebastian Murdoch-Gibson, Founder and CEO, QualRecruit, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, sebastian@qualrecruit.com

By Sebastian Murdoch-Gibson, Founder and CEO, QualRecruit, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, sebastian@qualrecruit.com

Interviewee: Bob Granito, President, IVP Research Labs. Morganville, New Jersey, bobg@ivpresearchlabs.com

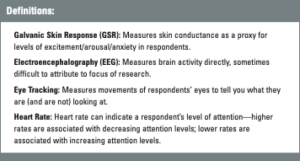

Can we really read a respondent’s mind? This seems to be the implied promise of emerging technologies in consumer research like facial coding, sentiment analysis, eye tracking, electroencephalography (EEG), Galvanic Skin Response (GSR), etc. If not a transparent window into the mind, these technologies promise access to consumer truths that remain unspoken, finding expression instead in a subtle eye movement or a heart-rate change. It’s an intriguing idea but, if you’re anything like me, it can be hard to wrap your head around the basics in this space.

What do we even call this emerging toolbox? Nonconscious methods? Implicit testing? Neuromarketing? What tools does it contain, and what do they do? Where did this technology come from, and where is it heading? Most importantly, what can all of this do to improve insights?

To clear these muddy waters, I sat down with Bob Granito, president of IVP Research Labs and one of the pioneers in bringing neuro methods to the insights industry. Our conversation traces the emergence of these research tools from his early application of television technologies to usability studies in the 1980s to the current state of the field.

Sebastian: Tell me a little bit about how you got into market research.

Bob: I started off after graduating college as a TV and film major, working for a TV station in New York City. I had no idea what market research was or anything about it; I was just a TV guy. But I quickly found out that I needed to go into another industry because the television industry was not very promising. I found an ad that said a large consumer bank was looking to build a research lab, and they were looking for a video technology guy to integrate video into the market research process. I had no idea what that was about, but I answered the ad and, lo and behold, it was for Citibank. I found out they were building this state-of-the-art research facility in midtown Manhattan. They wanted to be on the forefront of technology to help develop their interactive products.

I got the job, and they said, “OK, we’ve got this really big facility, and we want to put video everywhere. We want to see how somebody interacts with a home-banking device” or what they called at the time, an “Enhanced Telephone,” and all these technological things, including ATMs.

What I did for the six years I worked at Citibank was integrate all this technology with market research, which was pretty similar to what I do today.

Sebastian: What were the earliest technologies you were involved with to bring them into research, and how did that enhance insights at the time?

Bob: At Citibank, we replicated what they had at a TV station. So, we had a full television control room with tons of equipment, consoles, and monitors. There were six rooms that we would test in, and one was a bank branch. They literally built a simulated bank branch in the facility, so if you walked in, you’d think you were on the streets of Manhattan.

In that branch there were ceiling-mounted cameras everywhere that could be controlled remotely from the control room. We would custom-fit these cameras inside the ATM so we could capture the respondents’ facial reactions and more. We also had what they called at the time “scan converters,” so we could take the screen of the ATM and replicate it on video [as the respondent interacted with it].

Crucially, after using, let’s say the ATM machine, the team would conduct a follow-up interview to say, “I noticed you had trouble navigating this,” or “you looked a little frustrated at this point.” That would enable a discussion based on what the researchers were observing as it was taking place. We still do that today. Obviously, we use different technology, but the basic approach has not changed since my days at Citibank.

Sebastian: When you entered the market research industry, we were still working on integrating video into usability research. Where were neuro methods at that point? How did they evolve?

Bob: When I started my company, we were really just capturing observations of a respondent’s interactions. There was no number crunching going on. It was just like, “I’m going to watch this video, and I’m going to see how this person navigated an ATM screen.”

Then eye tracking emerged so we could capture the observational interaction, but we could also see it through the eyes of the respondent. We could see exactly where they’re looking, not only what direction, but we could pinpoint where their eyes are looking. If they’re walking through a store, we can see which signs they see. If they get to a shelf, we can see what product on the shelf they see first, what product they see second, and what product they don’t see. With eye tracking, what’s often really important is what they don’t see because you want to know what’s being overlooked.

The industry adopted eye tracking, and don’t get me wrong, it didn’t take overnight. It took three to four years before eye tracking became a mainstream methodology that clients decided to adopt and ask for.

It went from observational research to observational and eye tracking. That’s when we introduced neuro data collection methods to capture emotional responses or something behavioral like facial coding to measure facial expressions.

So now, we have all these types of measurements that you can call upon to really zero in on a user’s experience. We know everything about a person as they’re trying to complete an exercise or task. What they see, what they don’t see, how they feel when they’re going through it. Are they frustrated? Distracted? Interested?

Now that we have data on skin conductions, heart rate, facial coding, and brain activity, there are so many different paths to go down. It all comes down to what the client is trying to accomplish with the research. Certain methods will capture certain types of data. Some of it will be applicable; some of it won’t be.

Sebastian: When we talk about methodologies like EEG, facial coding, and eye tracking, there are various terms used to describe this host of tools— “implicit testing,” and “neuromarketing,” “nonconscious measures.” Is there one you prefer?

Bob: “Neuromarketing” is the term I like to throw out there. Neuro means we’re capturing some type of response from the brain.

It can be a direct response, meaning we’re doing a headset EEG; capturing the neurological response directly through the central nervous system by putting sensors on the scalp of the respondent. In that case, we’re capturing their brain activity directly.

But then, there’s neuro where you can capture the brain activity peripherally. So, we’re not going to capture your brain recordings directly; we’re going to capture the physiological response of different parts of your body that react to whatever stimuli is presented.

For example, measuring heart rate can tell us if you’re being more attentive, less attentive, and when that is happening. When the heart is accelerating or decelerating, that translates to levels of attention. Skin conductance can tell us someone’s levels of arousal or excitement. We can capture emotional valence by putting some sensors on a participant’s face to capture their facial muscle activity through facial electromyography.

All of that is being driven by the brain, but it’s being captured peripherally. Believe it or not, this is actually easier to interpret than studying the brain directly.

Because the brain is so complicated, it’s easy to capture data about it, but it’s hard to look at it and try to pinpoint why the responses are happening the way they are.

Let’s say we have a respondent driving in an autonomous car, and the client says, “I want to do EEG; I want to capture brain activity.” We can do that with the headset. But we don’t know what happened before they sat in the car. Maybe they had an argument with their spouse before they got in the car. So, they’re being driven by this autonomous car, but they’re really thinking about that argument they had the night before. That’s where it becomes challenging to interpret what you are looking at and making sure that there’s a correlation between the data and what’s being experienced.

When somebody sends me an email, whether it’s a client reaching out directly or a research consultant, my response is always, “what are you trying to learn from the research?” Because that’s going to dictate everything that happens after that. In this autonomous driving study that I just mentioned, they initially said they wanted to capture heart rate. Heart rate is only going to capture levels of attention. So, I’ll say, “OK, so they’re sitting in the back of the car, and the car’s driving them. What are we going to really get out of their attention level?”

We’d recommend going with Galvanic Skin Response (GSR), which measures levels of arousal, excitement. I think that’s what they really want to know. For example, are respondents paranoid? If everyone in the car has super anxiety throughout the whole experience, then obviously, that’s going to affect whether or not they feel comfortable getting in an Uber that might drive them without a driver.

Sebastian: You’ve brought up this technology, GSR, a couple of times. The mental image I’m starting to conjure is something that almost measures goosebumps on your skin or if your hair is standing on end—am I in the ballpark?

Bob: Yes, absolutely. GSR is a measure of your sweat response, so sweaty palms mean your arousal level is way up there. Physiologically, it’s telling you something. That’s how we measure levels of arousal and anxiety. We’ve done autonomous driving studies in the past with GSR where they drive the car and then the car drives them. The skin conductance levels are significantly different. In one scenario, they had total control, and in the second scenario, they had zero control.

Sebastian: When we think about what is on the cutting edge of neuro methods and how things might change in this part of the industry, what do you have your eye on?

Bob: A lot of things are going to stay the same. We had a two-year gap where we didn’t do a lot of in-person research, so, now, we’re doing a lot of catch-up. We haven’t had a one-on-one interview for at least two and a half to three years. A lot of the technology hasn’t changed because it’s been mothballed for years. We’ll probably just see an increase in volume.

The thing that has changed, and this is for the better of the industry, over the last two and a half years is a lot of this data collection technology has been moved online.

Now you can do online eye tracking, you can do online facial coding, and you can do online biometrics by capturing GSR and things like that. The eye tracking and the facial coding are no-brainers. They’re just using a computer’s webcam to capture a respondent’s eyes, the same way you’re capturing mine right now, to capture their face. Just video. If I laugh, you can figure out what that means, and the software will help you figure out what that means. When you get to GSR, it’s a little complicated but it’s out there.

So, the next big thing is going to be the transition to online. All of these things are going to get better and better and probably less expensive. That’s where I see the industry heading. The one thing I would like to emphasize is that anything done online usually comes at a cost in terms of compromise. Because of the nuances of in-person versus online research and the logistics involved, you are not getting the same quality responses and level of interaction. So, although technology is advancing, we have to consider the caveats.

Sebastian: What do neuro methods enable us to learn about consumers that we can’t learn through conventional methods? What are the kinds of insights that it gives us access to?

Bob: All the things we’ve been talking about, all this technology, all this data collection, really depend on the self-reporting methods as well. It’s not enough for the data to stand alone. Data only tell you so much and, most of the time, they tell you “the what.” They tell you what happened. While I navigated something I had a spike in my arousal level, or I had a significant amount of brain activity in my frontal lobe. It tells you, “OK, that’s what happened. Here’s the threshold, and here’s when it happened.”

What it doesn’t tell you is “the why.” You have to take all these data, and you have to try to marry them to “the why.” So, self-reporting is a critical part of the process. It’s the other half.

That being said, some clients are happy with “the what.” They just need to know when it happened. When we did the Super Bowl study, we really just wanted to know where the commercials resonated, so we did the GSR with 20 people in a bar. When the commercials came on, we could see where the GSR levels were elevated or if they stayed where they were. That’s all the client needed to know—what resonated based on the arousal level during this commercial. But there was no exploration of “why.”

Sebastian: This reminds me of the classic relationship between quant and qual. Quant tells you what; qual tells you why.

Bob: Absolutely. That’s why most of the research we do is qual-based. All the time clients will ask, “How many respondents can we do in a day?” When we say, “you can do eight to ten respondents in a day,” they’re like… “Wow, only eight to ten? What if we put them in a group?”

We can do that. We can tell you what eye-gaze behavior looks like, for eight people simultaneously. We can give you that data, and you’ll have a lot of rich data, but you won’t have “the why” part because you just can’t probe eight people the same way you can probe one person at a time. At the end of the day, you’re going to get eight people to tell you an enormous amount of information based on their experience, or you’re going to get 24 people in groups who’ll tell you a lot less significant information on their experience. Usually, if I’m being honest, it’s just raised hands. That’s your data.

Be the first to comment