By Mark A. Wheeler, Principal, Wheeler Research LLC, Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, mark@wheelerresearch.com

One of our primary goals as qualitative consultants is to provide actionable recommendations to our clients. When crafting recommendations, we draw upon our general knowledge of the field and insights gathered from respondents who represent the audience that our clients aim to target. However, our recommendations can be significantly strengthened by integrating some of the key principles from the field of behavioral science.

In this article, I describe five well-established behavioral science principles that often play a large role when humans make decisions. These specific examples were selected because they are both simple to apply and also highly relevant to building the kinds of tactics and persuasive messages that our clients are looking for.

Some initial remarks about leveraging behavioral science:

- These principles work best under conditions of uncertainty—that is, when there is no obvious or well-rehearsed opinion or action. It is not likely that you could leverage a principle of behavioral science to persuade someone in 2024 to change their opinion on, say, ice cream or Donald Trump. But you can greatly influence their reaction to a new product offering, or to a new environmental campaign, or to any novel kind of decision where there isn’t a clear answer about what to do next.

- The behavioral science principles work largely automatically or outside of conscious awareness. Because our brains have evolved to efficiently process vast amounts of information when making decisions, we take many mental shortcuts, and it is simply not the case that we always “think” before we decide and act. This makes the mental shortcuts difficult or impossible to consciously override.

- The principles listed below are well-established in behavioral science and only represent a small sample of what is out there (although I’ve picked the ones that I think are some of the most useful tools). For further background on these principles and examples, some of the best references and resources are listed in the call-out box below. Another faster option is to just search online for more information because these ideas are well described and have been applied successfully in many diverse contexts.

1. Social Proof: We Look to Others

Social proof is the idea that we tend to follow the actions of others, implicitly assuming those actions are correct in a given situation. When applied to marketing or selling, it means that showing potential customers what others have done can be a powerful persuasion technique.

One of the earliest and most notable examples came from scientist Robert Cialdini and his research team. Their goal was to encourage energy and water conservation by convincing hotel guests to reuse towels rather than have them washed each day. Some guests got nicely crafted messages on cards in their hotel rooms with the theme of helping “save the environment.” A second group saw a card promising that the hotel would make a donation to an environmental group for each reused towel. A third set of hotel guests read that “almost 75 percent of guests use their towels more than once” to help save environmental resources.

The results showed a large and significant uptake for those guests who received the message with social proof data—that is, the message telling them what other guests had done. In a later study, the researchers changed the message to guests who stayed in that particular room and found an even greater jump in towel reuse. The more similar the social comparison, the stronger the effect.

The use of social proof has been shown to influence behavior in a large (and growing) number of situations. It is also fascinating because it is often counterintuitive—probably only those who are familiar with behavioral science could have plausibly suggested this tactic for reusing towels. It probably seems to most people that the “rational argument” approach would have been the best way to go, but it wasn’t.

Qualitative consultants should begin leveraging evidence of social proof into their recommendations to clients. Potential customers are more likely to adopt a product when they see (or hear about) their peers using it—such as the tactic for environmental campaigns and for product launches (e.g., “your peers and neighbors have begun using our product”), as well as medical launches (e.g., have doctors hear from their colleagues about their successful adoption of a new medicine).

2. Loss Aversion and the Endowment Effect: We Love What We Have

One of the first and fundamental principles in behavioral science is that we place a higher value on avoiding losses than on acquiring equivalent gains. Coined by psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, the term loss aversion suggests that we are highly sensitive to the potential for losses and that we try to avoid the emotional impact of loss, whether it involves losing money, possessions, or even intangible benefits like familiarity or comfort.

Differently put, it “hurts” when we feel like we either lost something or are just about to lose something. If this sounds obvious and uninteresting, it isn’t—this is a robust effect that drives a great deal of our decision-making, even more than most of us realize.

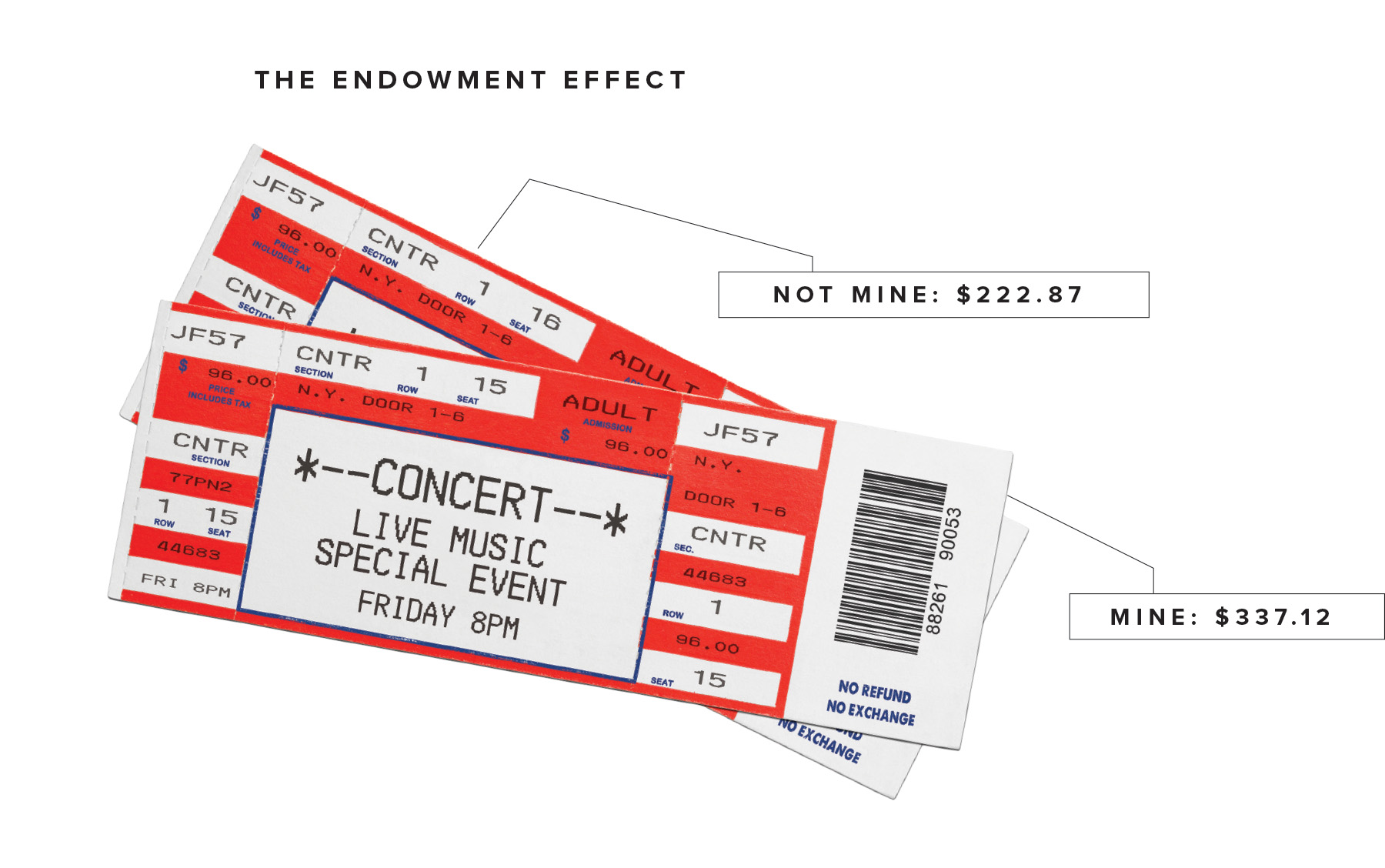

The phenomenon has been demonstrated many times across very different settings. When participants in psychological experiments are given something (e.g., concert tickets, shares of stock), they are rarely willing to sell those things for the same price that other people would be willing to buy them. This last example is also referred to as a case of the endowment effect—we assign a higher value to items we own compared to identical items that we don’t own. Once we feel that something is ours, then there is some level of hurt in parting with it that drives up the price we need to receive in order to let it go.

We are familiar with “loyalty” programs where customers earn rewards for their purchases (air miles or hotel points, anyone?). Once customers have established ownership of a certain number of points, the endowment effect makes it somewhat emotionally painful to just walk away from that brand by switching to a competitor, even when the competitor offers a better deal. These influences can be strong—we aren’t always thinking perfectly rationally when we accumulate or use our points given all the choices available.

In any decision, each individual option can be described in terms of either gains or losses. When writing marketing messages, it is a strong idea to emphasize what a potential customer can lose by not choosing your client’s product or service. The losses could be tangible benefits (e.g., specific features, money), less tangible comforts (e.g., loss of routine, perceived drug efficacy or safety), or merely the potential for losses (e.g., losing the chance to help the environment or losing the chance to feel better). Once the idea of a loss is activated in someone’s mind, the option attached to the loss becomes less desirable.

3. The Power of Telling Stories

There is overwhelming evidence, from both basic and applied research, showing that arguments are more persuasive when presented within a story. People are much more likely to donate to a charity when they hear stories with a compelling narrative, compared to more fact-based messages that describe the charity’s mission and actions. Similarly, mock juries respond more favorably to legal arguments when they are presented in a narrative or story format.

There have been multiple explanations offered for the robust influence of stories. A story is said to engage the audience emotionally while often putting listeners in relatable situations. Also, the structure of a narrative makes each individual component or fact easier to remember because it is embedded with other supporting information. Perhaps most importantly, a story allows the listener to be drawn into the narrative—they can absorb the story in a naturalistic way rather than feeling like they are being sold to.

Those of us in healthcare research have repeatedly heard our physician respondents tell us that, when a new drug is launched, they only want to see the clinical trial information (e.g., indication, safety, efficacy). Behavioral science findings strongly imply that this is not the approach that pharmaceutical reps should take—they should embed facts about the new medicine within a story. Of course, it can be a clinical story, e.g., how the new mechanism of action, or new molecule, or new route of administration leads to better outcomes.

This is a relatively easy behavioral science principle to describe and explain to clients. There is every reason to believe that the principle holds across a large number of contexts and marketing situations when presenting messages.

4. The Consistency Bias: We Don’t Want to Contradict Ourselves

The consistency bias refers to our inherent desire to remain consistent with our prior decisions, beliefs, and actions. This tendency probably comes from the motivation to avoid cognitive dissonance, which is the discomfort we feel when our beliefs don’t match our behaviors.

Many examples illustrate the power of consistency in driving action. When environmental groups advocate for green conservation habits, they may start by asking people to express their support for eco-friendly policies or practices. After people commit to the relatively low investment of signing a petition, they are then significantly more likely to agree to adopt environmentally friendly behaviors. Similarly, college students who are asked to pledge that they will vote in an upcoming election are indeed more likely to vote compared to other students who only heard messages about the importance of voting.

The implications for clients are fairly clear. They would be well served to have their customers find a way to publicly express positive feedback or actions consistent with whatever they are selling or requesting. When customers give the proverbial five-star reviews, they are not just providing feedback—they are also professing a “commitment” to their feelings about what they have just experienced, and they are more likely to turn to that product or offering again. Accordingly, the following ideas could be effective tactics for our clients:

- Asking potential customers to accept a free sample or trial before making a purchase

- Asking doctors (or patients) if they value a particular medical offering (of course, this works better when they do feel positively about it)

- Collecting signatures or other pledges of support for actions consistent with things you might request later

- Reminding customers of their past decisions or behaviors that align with the current choice that you are presenting

5. Applying the Principles Ethically

The principles of behavioral science work, yet I think that they are still consistently underutilized, considering their value. When I work with pharmaceutical teams, I often see bright, hard-working people trying to logically persuade doctors and patients to adopt their medicines (with, say, four different efficacy data points and a complex table of potential side effects). What psychology and behavioral science teach us, however, is that decision-making (even medical decision-making) is very frequently neither perfectly logical nor rational but influenced strongly by the above-mentioned principles and many others that operate largely independently of whether we are aware of them or not. (Just to be clear, this does not mean that doctors decide truly irrationally—it does mean that sometimes there are multiple possible reasonable options and that their prescribing decisions are subject to the same behavioral science principles as any other kind of decision.)

In the particular example I described above, it would be more useful for doctors to learn that their peer colleagues are successfully using a new medicine than for them to hear more about the clinical trial data. This application of social norms would be even more persuasive if the doctors could see or hear from their colleagues directly.

Integrating behavioral science is a way that we qualitative consultants can help our clients align their strategies and messages with the ways that their customers decide and behave. In my experience, clients have been highly receptive to Recommendations sections, which briefly (a slide or less) describe a relevant behavioral science principle and then go on to suggest tactics (sometimes called nudges) that apply the principle.

As some behavioral scientists, particularly Robert Cialdini, have frequently mentioned, behavioral science should always be used responsibly and ethically. It is possible to “persuade” people unfairly a single time (say, by leveraging a principle in support of a shady sales proposition), but once they see it, this can lead to unhappiness, distrust, or the abrupt end of a working relationship. Behavioral science should be applied selectively and responsibly to help clients achieve their goals in a form that stays consistent with the clients’ publicly stated values. The long-term benefit of applying behavioral science is to help ethical companies promote their messages in a way that is consistent with how their customers are making their decisions.