By Michael Tucker, Ph.D.

Principal

MLT Research LLC

Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania 19004

mlt_research@proton.me

How I Got Here

How I Got Here

An impromptu straw poll at the 2025 QRCA Annual Conference in Philadelphia revealed that only a handful of those in attendance came to marketing research as an intended career. Most started elsewhere—in sales, in academics, in the social sciences, in business—and found the lure of market research enticing, and the ability to pose research questions that often have immediate results quite rewarding. For many, the rest is history.

I’m no different. I’m a cognitive developmental psychologist by training. I’m sometimes asked how that adds value to the work I do in qualitative research. Ultimately, whether we’re cognitive specialists or not, all researchers have a similar goal—understanding human behavior and providing insights in support of our clients’ business objectives.

The Problem We’re Solving: How Did They Get Here?

Marketers frequently face the challenge of dealing with consumer habits—entrenched behaviors among our customers that seem resistant to change. Frequently, our job is to identify these patterns of behavior and then figure out what the motivators might be to disrupt those patterns, so clients can persuasively move customers toward new behaviors (that presumably favor our clients’ objectives). My goal here is to propose a different theoretical approach to this problem of habitual or entrenched behavior, known as developmental systems theory, and the idea of attractor states. It’s a developmental approach, which asks the question: How did they get here? Because answering that question is sometimes how you can find the solution.

There are two concrete examples of habits I want to use to help illustrate both the problem, and how this approach can offer a solution. The two areas are the habitual prescriber in the health care space (where I spend most of my time), and the non-rejector, which is a problem more common in the consumer world.

I’ll start with the problems, then give you a summary of the theory.

Habits in Health Care

Habits in Health Care

I recently completed a project analyzing the prescribing behavior of primary care physicians treating a chronic condition. The condition can be managed with various options, including older treatments that are effective but have side effects, and newer treatments that face slow adoption due to habitual prescribing patterns. The client’s product was among these newer options, but doctors were hesitant to adopt it due to perceived hassle and costs. The client believed these habitual non-prescribers were unlikely to change. My role was to design research to understand their motivations and find ways to present the client’s product as a superior alternative for chronic patients.

A colleague at the recent QRCA Annual Conference provided our second example—calling it “cracking the nut of the non-rejectors.” These consumers are hard to persuade to try new products, but aren’t opposed either. They’re undecided, waiting to be convinced, but it’s unclear what will win them over. What motivates them? What aspects of the product or purchasing situation influence their choices, and to what degree? Often, like health care traditionalists or late adopters, marketers consider non-rejectors not worth pursuing due to low return on investment—“the juice isn’t worth the squeeze.”

So here we have two scenarios with deep-rooted, seemingly intractable behaviors that resist traditional marketing efforts. Clients wonder if they should give up on these customers entirely. However, I think viewing them through dynamic systems theory, and the concept of an attractor state might offer a new way to reshape the habit. Understanding how the habit formed initially is crucial.

The Theory

Dynamic systems theory (or developmental systems theory) uses mathematical approaches to study changes in behavioral systems over time. It is applied in many disciplines, including mathematics, engineering, economics, physics, meteorology, psychology, and biology. I previously used this theory to explain language acquisition, speech perception, and music perception in infants.

In marketing research, it helps to understand behavior changes, consumer analysis, and trends, optimize strategies, and evaluate policy impacts, like regulations on consumers. Though it can be complex and mathematical when applied, it does not have to be.

The approach contains three key aspects that are important for us to focus on here, and I’ll explain each in turn.

The approach contains three key aspects that are important for us to focus on here, and I’ll explain each in turn.

- Sensitive dependence on initial conditions: the earliest influences that lead to the development of the system can be critical to understanding how it develops and why it persists.

- Self-organization and emergent properties: systems of behavior can emerge without the intention to create those systems, and behaviors may develop spontaneously based on the interrelations of key influences.

- The strange/stable attractor: systemic behaviors are often patterned in what are called attractor states and tend to persist this way unless great effort is exerted to change them (a phase shift). This last one is important as we discussed habits earlier.

Let’s take these individually

- Sensitive Dependence on Initial Conditions

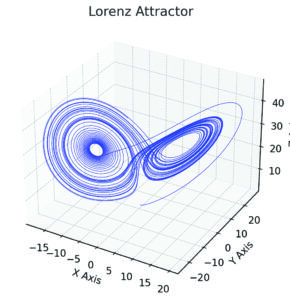

Edward Lorenz, an American mathematician and meteorologist, coined this term in the 1960s. He found that nearly identical initial weather conditions could result in vastly different outcomes, making long-term weather prediction almost impossible beyond a certain period of time. His work revealed that what was thought to be predictable was actually chaotic. The “Lorenz attractor,” or the “butterfly effect,” suggests small changes can lead to significant impacts over time, like a butterfly flapping its wings in Idaho causing a hurricane in Tokyo.

Edward Lorenz, an American mathematician and meteorologist, coined this term in the 1960s. He found that nearly identical initial weather conditions could result in vastly different outcomes, making long-term weather prediction almost impossible beyond a certain period of time. His work revealed that what was thought to be predictable was actually chaotic. The “Lorenz attractor,” or the “butterfly effect,” suggests small changes can lead to significant impacts over time, like a butterfly flapping its wings in Idaho causing a hurricane in Tokyo.

A simple example of habits that can result from initial small changes could be something as simple as a robust exercise routine that develops from a five-minute walk around the neighborhood, at the beginning of the day, versus one that starts, say, at lunch, or at work. The specifics of small changes in the appropriate environment, over time, can lead to behavioral persistency in sometimes unexpected ways.

What does this have to do with marketing research? Observing entrenched behaviors, like habitual purchasing or prescribing, can be partially explained by understanding the initial conditions that led to their formation—such as early influences, beliefs, and desires. Additionally, not all one-to-one relationships among these influences are straightforward; yet, they may still result in similar habitual behaviors.

- Self-organization and Emergent Properties

Systemic patterns are self-organizing, emerging often without the intention to create the system. This is an important consideration when talking about habits. Statements like “I don’t know why I’m drawn to this” or “It just seems automatic to me” suggest that some behaviors are automatic rather than thoughtful.

When discussing habits, people often think of bad ones, such as overeating sweets, compulsive shopping, doom scrolling on social media, or more harmful behaviors like bad relationships and substance use. These habits share one trait: they are behavioral patterns that feel out of our control and develop unintentionally.

Systems theory suggests that behavioral patterns are shaped by initial conditions and nonlinear (unpredictable) forces. These forces create and sustain behavioral systems over time, making them entrenched and self-sustaining.

For example, many of us may have developed certain behaviors during the COVID-19 lockdown: washing our hands with a vigilance (bordering for some almost on compulsion), keeping distance from others in lines at the store, “no-touch” ordering food or goods, even though the concern about physical contact has since been greatly reduced. These behaviors may reduce anxiety or produce reassurance that we are safe or secure. The habits, therefore, could persist and become automatic, even when they may no longer be necessary.

What’s the implication of this for market researchers trying to understand habitual behavior and attempting to disrupt or redirect it? How does this impact methodology and analysis?

- Understanding habitual behavior may require examining influences people are not aware of. We often explore nonrational motivators using projective techniques when respondents cannot explain their actions. These methods could be essential for understanding habitual behavior.

- We use attractors to describe behavioral influences that emerge over time but are less dominant now. The factors that formed the habit may have weakened, but they still play a role in the habit system.

Let’s unpack these things some more.

I’m using as an example some of the foundational differences among physician specialists that lead to differences in their prescribing behavior. They are important to understand, but may not be open to change or influence. What are some of the nonrational differences we see with physicians that impact their prescribing (sometimes in ways that they may not even be aware of)?

Consider surgeons versus rheumatologists. Surgeons are driven to identify and fix problems definitively, in short order. They find satisfaction in solving surgical issues relatively permanently. By contrast, rheumatologists act as detectives; they enjoy and are often required to unravel complex, mysterious disorders and tailor treatments to each patient’s needs.

Understanding the motivations of surgeons or rheumatologists, including why they chose their specialties and what drives their daily decisions, is crucial. Marketers can use this insight to disrupt established patterns. Crafting questions about their specialty choices and patient management satisfaction, and incorporating emotional techniques, may help researchers understand and influence habitual behaviors.

Similarly, depending on the product, consumers may have attitudes, beliefs, or feelings around household experiences or items (at the recent conference, the question of early memories of doing laundry came up). Those powerful emotional associations may have helped in the formation of later purchasing behavior, even if consumers are not aware of them, and even if they do not carry the same weight today as they might have before.

Again, understanding some of the “initial conditions” of the behavioral system can go a long way toward explaining its persistence over time.

- The Strange/Stable Attractor

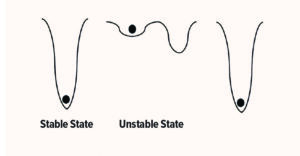

Dynamic systems theory suggests that certain systems can organize themselves under appropriate conditions, becoming stable and resistant to change without deliberate effort. Behavioral systems have “attractor states,” stable patterns akin to habitual behavior. These systems can switch from one stable state to another through a “phase shift”—thus reorganizing—influenced by energy input and current level of stability.

This diagram effectively shows stable attractors and phase shifts. A ball in a shallow well (attractor) easily moves to the next one, while a ball in a deep well needs more effort due to gravity and friction. Think of the attractor as a behavior pattern. The “force” might be information about the product, opportunities to use it, positive feedback, perceived value, success, consistency with values, etc. These motivators help move behavior from a deep habit “well” to another stable state.

This diagram effectively shows stable attractors and phase shifts. A ball in a shallow well (attractor) easily moves to the next one, while a ball in a deep well needs more effort due to gravity and friction. Think of the attractor as a behavior pattern. The “force” might be information about the product, opportunities to use it, positive feedback, perceived value, success, consistency with values, etc. These motivators help move behavior from a deep habit “well” to another stable state.

In my earlier health care example, I talked about a client who was trying to figure out how to break prescribers’ habits around a particular treatment area. I presented this example at the QRCA AI Days (July 2024).

The research aimed to identify prescribing habits and find ways to influence them toward the client’s product. We advised the client to consider practical factors (formulary status, generic options), professional factors (clinical profile awareness), and psychological factors (perceptions of being a “good doctor” and relationships with patients in this treatment category).

So, as marketers, let’s think of these habitual behavior constellations as attractor states, in a “deep well.” In this way, we should also assume that the forces needed to dislodge or alter them (messaging campaigns geared toward changing attitudes, positioning strategies that address biases toward products or patient types, or leveraging triggers of alternative selection or prescribing behavior) will need to be repeatedly and consistently applied.

Tying It All Together

I suspect this sometimes complex, theoretical approach might significantly improve market research, particularly when addressing challenging problems researchers face. It offers new ways to view problems by examining behavior development longitudinally to identify disruptions and malleability.

We need to consider various influences beyond usual factors when analyzing motivations or inhibitions of behavior. This approach favors specific research methodologies, especially nonrational/emotional ones, as behaviors may stem from unconscious reasons requiring thorough investigation.

Final Thoughts and Implications

There is no one-size-fits-all approach, and I’m not suggesting this method applies to most or even many research problems. “Development” isn’t just change over time. For instance, the African violet in my office expiring slowly despite my best efforts, wasn’t developing, but it was certainly changing. Development involves meaningful interactions with our world that shape our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, which, in turn, influence future interactions. Not all change is developmental, nor is all development dynamic systems development.

Systems theory offers a different way to think about behavior by viewing crucial behavior patterns from a longitudinal perspective. It encourages us to recognize that behaviors we study, such as consumer choices or prescribing habits, may not be intentional despite appearing persistent. To understand and motivate changes in these behaviors then, we might need to consider a broader range of influences. This approach could provide richer research results, when viewed through a different lens.

Or, as David Byrne of The Talking Heads famously pondered, “How did I get here?” Asking that question in our research might take us further than we thought.